A multi-color version of Petunia Pullover, a sideways knit sweater designed by Ainur Berkimbayeva for Purl Soho

Read MorePrincess Leia's Knitted Wig

Make your own knitted wig to complete your Princess Leia outfit for Halloween!

Read MorePYRAMIS PATTERN'S TEST-KNITTERS

Melissa’s Pyramis

Size 3 on 37”/94cm bust and 42.75”/109cm hip

Yarn: Premier Cotton Fair - it is soft, drapey, heavy, but it stretched out after a few wears.

Yardage: 1100 yards/1005 meters

Modification: Added 2 inches (20 extra sts)

Notes: May make a smaller size next time.

Finished measurements: Hip - 43”/109cm (became 46”/117cm after a few wears), chest - 59.5”/151cm (became 58”/147cm after wear). body length - 23”/58.5cm

Click here for Melissa’s Ravelry project page. She is also on Instagram at MisLisKnits.

Catherine’s Pyramis

Size 1 on 36.5”/93cm bust and 36”/91.5cm hip

Yarn: Purple color is Classic Elite Telluride - 82/12/6 percent alpaca/linen/Donegal

Green color is Universal Yarn Wool Pop - 50/35/15 percent bamboo/superwash wool/polyamide

Yardage: 330 yards/302 meters of each color

Modifications: She knitted it with a looser gauge (17.5 sts x 34 rows), so the finished top turned out bigger. Also, Catherine knitted three rounds of 1x1 twisted rib all in purple color.

Finished measurements: Hip - 40”/102cm, chest - 48”/123cm, body length - 18.5”/47cm.

Click here for Catherine’s Ravelry project page. She is also on Instagram at Catherine_this_life

Olha’s Pyramis

Size 2 on 35.75”/91cm bust and 37.5”/95cm hip

Yarn: Luxury Selection (90/10 cotton/silk) and Silvedd Filati (100% silk). These yarns are drapey, so the top’s hip stretched out.

Yardage: 470 yards/430 meters of grey and 427 yards/390 meters of rose

Modification: worked the neck’s I-Cord with smaller needles

Finished measurements: Hip - 46.5”/118cm, chest - 53.5”/136cm, body length - 19.75”/50cm.

Click here to see Olha’s Ravelry project page. She is also on Instagram at Olhareva

Anne’s Pyramis

Size 1 on 34.25”/87cm bust and 37”/94cm hip

Yarn: Noro Silk Garden Sock, Grignasco Champagne

Yardage: 220 yards/201 meters of each yarn

Modifications: none

Finished measurements: Hip - 37½”/95.5cm, chest - 51½”/131cm

Click here to see Anne’s Ravelry project page. She is also on Instagram at Anneswolle.

Kristina’s Pyramis

Size 5 on 47.75”/121cm bust and 47.25”/120cm hip

Yarn: Amy Butler Belle Organic DK from Rowan, 50/50 percent wool/cotton

Yardage: 1179 yards/1078 meters in the garment, the finished garment weighs 449g.

Modification: Added bust dart as suggested in the pattern

Notes: Gauge was spot on on the gauge swatch, but the garter stitch row gauge really stretches out in a large garment even if blocked smaller

Finished measurements: Hip - 53.5”/136cm initially, 56”/142cm after wear, chest - 67”/170cm initially, 63”/160cm after wear, and body length - 20.5”/52cm initially, 22”/56cm after wear

Click here to see Kristina’s Ravelry project page. She is also on Instagram at Spinnkrok.

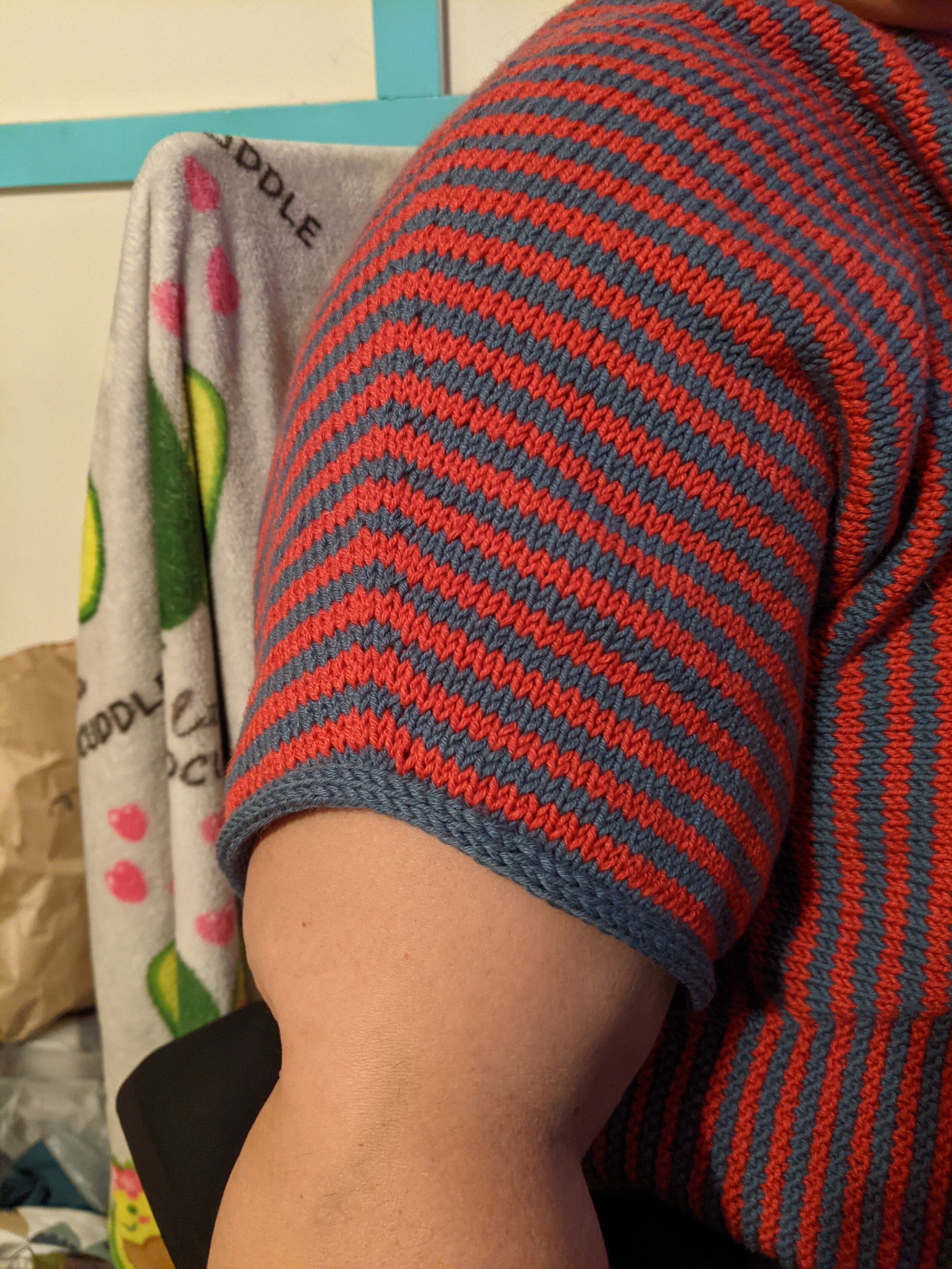

Cesca’s Pyramis

Size 2 on 35.5”/90cm bust and 37.75”/96cm hip

Yarn: Juniper Moon Farm Patagonia Organic (Sport weight, 100% wool) and De Rerum Natura Ulysse (Sport weight, 100% wool)

Yardage: dark color - 458 yards/419 meters and light color - 466 yards/426 meters

Modification: added 3/4 sleeves, used provisional crochet cast-on to work a 3-needle-bind-off on the side seams and to have live sts for the armhole finishing

Finished measurements: Hip - 41.25”/105cm, chest - 49.5”/126cm, and body length 20.75”/52.5cm

Click here to see Cesca’s Ravelry project page. They are also on Instagram at FelixAguilarCrafts.

Melissa’s Cropped Pyramis

Size 4 on 42”/107cm bust and 46”/117cm hip

Yarn: Neighborhood Fiber Co's Capital Luxury Sport yarn (80/10/10 percent merino/cashmere/silk) - the yarn is smooth and soft with some drape.

Yardage: 434 yards/397 meters of the darker color and 462 yards/422 meters of the second, lighter color

Modification: added 2 rows of the second color at the side seams to continue the pattern, omitted the neck I-Cord

Notes: should only add a single row on one edge next time, so as to make one row of the second color, then add the second row with mattress stitch

Finished measurements: Hip - 54”/137cm, chest - 56”/142cm, and body length - 18”/46cm

Click here to see Melissa’s Ravelry project page. She is also on Instagram at MG.wears.things.

Beth’s Pyramis

Size 7 on 44”/112cm bust and 56”/142cm hip

Yarn: Cascade Yarns Anchor Bay - it has form without being too stiff.

Yardage: 1300 yards/1188 meters

Modifications: none

Notes: The top fits bigger than expected

Finished measurements: Hip - 65”/165cm, chest - 78”/198cm, and body length - 21”/53.5cm

Click here to see Beth’s Ravelry project page. She is also on Instagram at SchuffBeth.

Flying Home Top Pattern Release and Test-Knitters' versions

Flying Home Top is finally ready for its release and I would like to take a moment to chat about the pattern itself, the amazing pattern testers, and their versions of this top.

First off, the top you see on the pattern cover page is Size 2 modeled by me (my upper bust is 33”/84cm and full bust is 35”/89cm). I have about 7.5”/19cm of positive ease around my full bust, but it doesn’t look like it, does it? It’s because the tucks get longer towards the center and each tuck gradually adds more ease to the front and creates an A-line shaping. The top is knitted sideways, with the front worked in two pieces sewn in the front center and the back is worked as one piece. The sides are seamed with mattress stitch.

The pattern includes notes about adjusting sizes for bigger cup sizes and adding length to the top in general or just the front by adding bust darts.

I knitted this sample with Seismic Yarn Cellular in Thai Ice colorway. This base is a 60/40 percent blend of organic cotton and linen. This yarn costs $28 per 100g skein, and I used 2 skeins of it, so it was $56 total, plus shipping. I loved knitting with this yarn as it was soft (for a linen blend yarn), round, dense, and drapey. I also liked that it’s not very slippery like the 100% linen yarns I have tried. It felt very much like knitting with cotton, but it is definitely drapier than pure cotton, and drapiness is what I was after for this design!

I also made a second sample using a more affordable yarn - Knit Picks’ Lindy Chain. The content is very similar to the previous yarn; it’s also a blend of cotton and linen, but there is much more linen here (70% linen and 30% cotton). Plus, the yarn has the chainette construction. While I was able to get the gauge and I love this Turmeric colorway (btw there’s a lot of colors to choose from), knitting with this yarn was a bit tricky. I kept snagging the individual strands of the yarn and had to be very attentive and careful, which meant my knitting slowed down significantly. Despite that, I think this is a great value for the price ($6.99 per 50g ball). I used 4 balls of this yarn, bringing the total yarn cost to $28, plus shipping.

Ok, now let me tell you about the amazing pattern testers and their Flying Home Tops!

1. Tara’s Flying Home Top

Tara used Knit Picks’ Lindy Chain in Urchin colorway. She knitted Size 5, and she’s wearing it with 4”/10cm of positive ease around her full bust. She didn’t make any modifications to the pattern, which was a great decision because the top looks fantastic on Tara! Click here for Tara’s project notes on Ravelry and here to see her Instagram feed chock-full of beautiful knits!

2. Anne’s Flying Home Top

Anne used her own Little Skein Pianta (this base is not available yet), a yarn base that is identical to Seismic Yarn Cellular. And, because she is an amazing yarn dyer herself, she dyed this gorgeous shade of pinkish-beige colorway called Apple Blossom. She knitted Size 3, and she’s wearing it with 6”/15cm of positive ease around her full bust. She didn’t make any modifications to the pattern either. You can find Anne’s project notes on Ravelry by clicking here. Be sure to check out her yarny Instagram feed!

3. Jasmin’s Flying Home Top

Jasmin used Tess Yarns Raw Silk, which is a 100% silk yarn. This is the Mango colorway and it totally lives up to its name! Jasmin knitted Size 4, and she’s wearing it with 6.75”/17cm of positive ease around her full bust. Because Jasmin’s stitch gauge was slightly different than the one in the pattern, she decided to adjust her stitch count to make sure she got the necessary length (because the top is knitted sideways). To see more of Jasmin’s knits, check out her fun, colorful Instagram pages here and here. Jasmin is also a host of the Knit More Girls podcast, a multi-generational knitting production.

4. Rachel’s Flying Home Top

Rachel used Knit Picks’ Lindy Chain in Turmeric and Conch colorways. She wanted to use up the leftover yarn balls from her stash and that’s how she came up with this fun way of color-blocking her top. She knitted Size 1 with no modifications, and she is wearing it with 3-4”/7.5-10cm of positive ease around her full bust. You can find Rachel’s project notes on Ravelry by following this link. Rachel also shares her knitting and sewing projects on her Instagram page.

5. Emily’s Flying Home Top

Emily knitted her top with Seismic Yarn Cellular in Dragongruit Punch colorway - isn’t it the perfect name for this color?! She knitted Size 2, and she’s wearing it with 8.5”/22cm of positive ease around her full bust. Emily wrote up lots of helpful notes on her project page on Ravelry - be sure to check it out! Emily also shares her knits and other makes on her Instagram page!

6. Julia’s Flying Home Top

Julia used a 100% viscose yarn with an output of 320 yards per 100grams. She enjoyed working with this yarn because it is soft and pleasant to wear in the summer, but the top stretched lengthwise quite a bit after washing. To get the correct gauge, Julia used needles one size bigger than recommended as she knits more tightly (she used US 4 / 3.5mm). She is wearing Size 1 with 7”/17.5cm of positive ease around her full bust. To see Julia’s project page on Ravelry, click here. To see more of her knits, check out her Instagram page here!

7. Josephine’s Flying Home Top

Josephine knitted this top while learning Portuguese knitting! If you’re not familiar with this method, read up on it here - it’s quite fascinating! Apparently, it is great for people who have arthritis or carpal tunnel syndrome as it involves minimal hand movement. Anyway, back to Josephine and her top: she used Seismic Yarn Cellular in Rhubarb colorway. She made Size 1 and she’s wearing it with about 5”/13cm of positive ease around her full bust. Josephine cast on both sides of the front at the same time, which I think is a terrific idea for keeping the gauge consistent and making sure both sides are symmetrical. However, she did not enjoy the Kitchener stitch in the front center and is planning to make another version of this top where she will work the front as one piece (rather than two pieces sewn in the middle). I think that’s a great idea to try out, but it will make all the pleats face in one direction instead of symmetrically radiating from the center front. I think it will still look beautiful, and if you can’t stand the Kitchener, it’s definitely a good modification to this design! By the way, click here to see Josephine’s project page on Ravelry and check out her Instagram page here (so many yummy pictures of food)!

8. Melissa’s Flying Home Top

Melissa knitted her top using Seismic Yarn Cellular in Evoo colorway - and I’m so in love with it! Melissa knitted Size 3, but because this was her first time working with a linen-blend yarn, getting the right gauge was difficult and the top turned out bigger than she expected. I think the top looks beautiful on Melissa - it has a beautiful loose/breezy vibe! Check out Melissa’s project page on Ravelry and check out her Instagram where Melissa shares all her knitting, sewing and cooking!

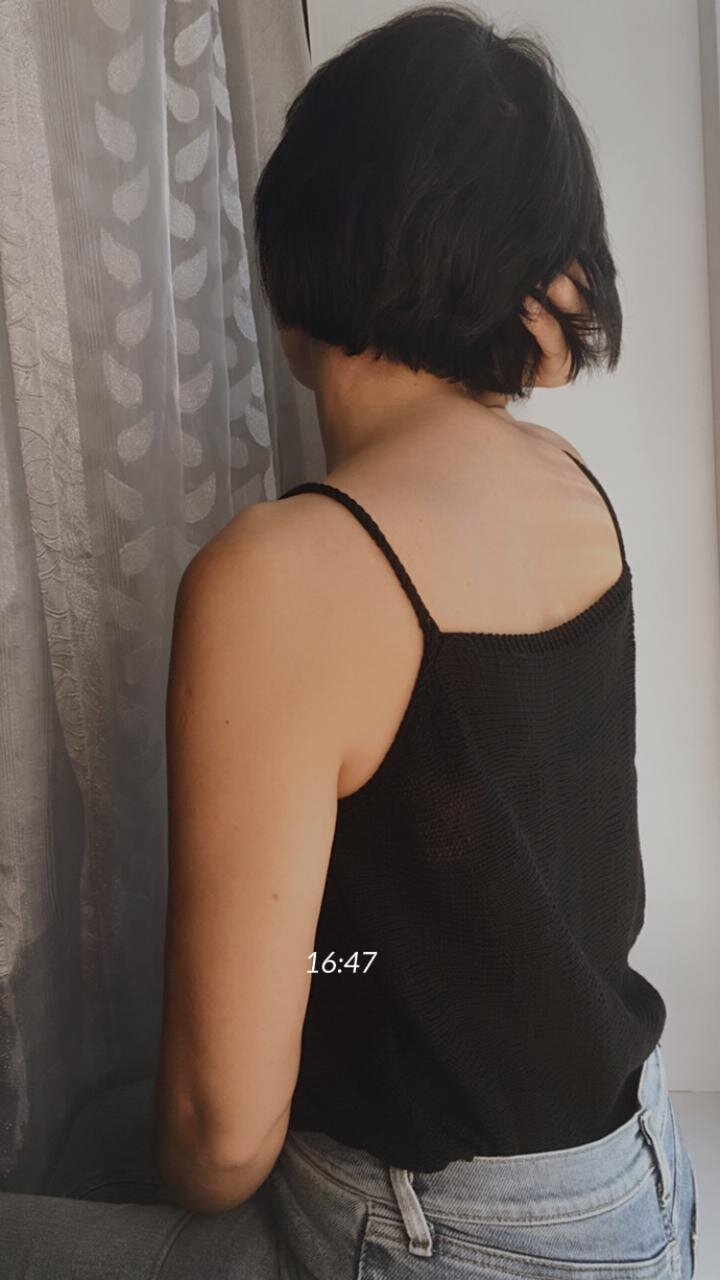

9. Kim’s Flying Home Top

Kim knitted her top using KPC Yarn Gossyp 4ply, a 100% organic cotton yarn, in Midnight colorway. She knitted Size 2 and she’s wearing it with 6.5”/17cm of positive ease around her full bust. Kim made the straps .5”/1cm longer than recommended, but her top and straps stretched more after wear, so she plans to make the straps shorter for her next top (she’s already knitting another Flying Home Top in a different color). Click here to see Kim’s project notes on Ravelry. Kim is also a knitting instructor based in Hong Kong, so if you’d like to book a lesson/workshop with her, check out her business page on Facebook!

Nightshades collection by Whitney Hayward

Interview with Whitney Hayward: knitwear design as a career

Hi Whitney! I’m so happy you agreed to sit down with me and chat about knitwear design and what goes on in the world of a talented designer like yourself.

Could you tell a bit about yourself, how you got into knitting and designing knitwear, and how you started working for Harrisville Designs?

Sure! How I got into knitting: I’ve been knitting since 2010, a skill I picked up from my host family when I was living in Japan for a language study in Nagoya. I was especially terrible at reading Japanese, and I wanted to better connect with my host mom Kazumi, who seemed to know how to do a little bit of everything. Once the weather started to get a bit cooler that year, she started knitting a scarf, and for whatever reason I thought that learning how to knit might help me with my feeble Japanese reading comprehension. It did, and I will never be able to say thank you enough to her for teaching me a skill I hope to use for the rest of my life. It was hard to learn how to read western patterns after learning how to read Japanese patterns, though! I love the way Japanese patterns are written in schematic form, vs fully written.

How I started designing knitwear: I continued knitting after leaving Japan, but definitely treated it as a fun hobby that I occasionally picked up, focusing more on journalism. I graduated from my university, and got a job at a mid-sized metro newspaper in Portland, Maine as a staff photojournalist. I loved, and still love, print journalism. I worked for an incredible photo editor, Yoon Byun, who I was lucky to learn from at an early age in my career. My photography would be much crappier if I hadn’t! Despite the best circumstances at the paper, a few years in, I started to feel myself change, both internally and externally. Fires, court, homicide, were all possible daily assignments, and the uncertainty of what the day would hold gnawed at me from the moment I woke up. The entire state of Maine was our coverage area, and I was driving close to 35,000 miles a year; my car felt like my home sometimes! This is when I started to knit voraciously, and would rarely be seen without my knitting, as I was absolutely using it as a coping mechanism. The downtime in the car, combined with the need for a mental distraction, was a perfect reason to non-stop knit. This eventually transitioned to me tinkering with designing out of curiosity, and self publishing a few designs, which, I can admit, did not go well if we’re judging by whether they made me any money! Despite that, I eventually met the people at Quince & Co., who are also based in Portland. At the time, I felt like I was hanging by a thread at the paper, and was incredibly fortunate that they were looking for a new in-house photographer, and someone to help out at Twig & Horn, their side knitting notions company. I quit journalism, and dove headfirst into the knitting industry, eventually starting Stone Wool with Quince. Leila and Dawn at Quince were so foundational to me learning how to be a better knitwear designer, and I’ll never be able to repay them enough for all of the knowledge they imparted.

After working at Quince for a few years, I started to desperately miss my family back home in Missouri. My partner has family who lives in Arkansas, and we decided to move back home so we’d be able to visit more often. I left T&H and Stone Wool in incredibly capable hands, and decided to give a try at going freelance. Harrisville yarns (frankly, all woolen spun yarns) are my favorite to knit with, and I reached out to Harrisville to see if they were looking for any freelance designers. I reached out to them at a serendipitous time, as they were looking for a designer to take on a new project they were calling Nightshades. We both felt happy with how the partnership worked with that collection, and that freelance work transitioned into a job at Harrisville as their pattern director.

“Knitwear design (hand-knits design) is not a job, but a hobby” seems to be the common thread among many knitters/designers. What are your thoughts about that? Is it realistic to make a living doing knitwear design?

Yes, I’ve heard this too. I absolutely think knitwear design can be a hobby, or part-time work, for designers—I think that’s a-ok! However, the idea that knitwear design is exclusively a hobby activity downplays the hard work required to make an accurate, well written pattern. It also illustrates a more troublesome part of designing, that many people (myself included) cannot make a full-time living from knitwear design alone.

I think there are two things underpinning this. One, the less serious one, is that most of us who decided to pursue knitwear design enjoy knitting. It’s natural to believe that knitwear design will be as fun and engaging as knitting. As you know, much of the actual work of pattern writing requires no knitting at all, rather math / spatial reasoning problem solving. Math is not a hobby for me, and I suppose most knitwear designers would fall under that camp. It’s hard work. Admittedly with not much quantifiable data to substantiate this belief, I think the perception of knitwear design as a hobby has influenced the average price of knitwear patterns, especially if you compare them to digital home sewing patterns.

The second, is that there’s a lot of veiled secrecy about what it’s like to pursue knitwear pattern design full-time, and what most people are making annually. I will pointedly say that I’ve never, ever, earned enough from royalties, publication rates, or self publishing to make a living wage when I’ve worked as a freelance knitwear designer. I’m individually responsible for funding my living expenses, rent, etc, and no way does my royalty-only money come close to meeting those bills. Anytime I’ve been fully freelance, I’ve always supplemented my income with photography assignments, freelance marketing/social media work, etc. Just to break this down a little bit, on average, around 30-50 people download each of my patterns, an average that accounts for some of my patterns that haven’t been so popular, and others that have been more popular than that range. Although I’m so grateful that one person wants to knit something I’ve made, and am worried this next bit will sound as if I’m scoffing at these download numbers, there’s no way I’m able to live on that income alone. Let’s say that a pattern gets 60 downloads, and the pattern is sold at $8/download. That’s $480, classified as self-employed 1099 income, which is taxed much higher than if I earned that $480 through an employer. Let’s then say that I could magically publish 1 garment pattern per week (which would be insane!)—I’d need to get those 60 downloads weekly, and assuming I’m trying to hit full-time at 40 hours per week, I’d be paying myself $11.25/hr, taxed way higher than that wage would be taxed if you worked for a company. This doesn’t even account for paying a tech editor to edit the pattern, compensation for test knitters, hiring a photographer, hiring a model, etc. In most all geographic areas in the United States, this is simply not enough income to pay living expenses in a single income, single person household.

I know I have a high amount of privilege, both as a white person, and also in the type of side work I’m able to take on to account for this lack of income, enabling me to continue as a knitwear designer. When I was fully freelance before working at Harrisville, if I didn’t have the ability to take on photography and other side jobs, I undoubtedly would have quit knitwear design for something more stable. Unless a pattern wildly takes off, and I hope I’m not overstepping or painting with too broad a brush in saying this, I don’t think the average designer is making a living wage on knitting patterns alone, without having a second household income, or taking on alternative work. It wouldn’t solve all of these factors at work, but this is partially why I think knitwear patterns should be priced similarly to PDF sewing patterns. If they were, I think it could possibly alleviate some, not all, of the problems making a living wage as a knitwear designer. I designed production sewing patterns and tech packs for Twig & Horn, and though that process is significantly different than designing a home sewing garment pattern, I can say that both take a comparable amount of skill, accuracy, and time. A garment digital pattern could easily cost $15, and to charge that amount for a knitting pattern is relatively unheard of.

What does your day look like as a knitwear designer?

I usually start work around 7 in the morning every weekday, catching up on emails, customer support and yarn support requests for Harrisville, and communicating with sample knitters. This usually lasts until noon or so, and after that time I work on my own patterns in development for Harrisville collections. This could mean grading math, pattern writing, sample knitting, editing photos, pretty much anything that relates to publishing a pattern. If I’m including sample knitting in this schedule, I probably work until 7 - 8 at night, and I usually sample knit on the weekend.

Approximately, how long does it take to design, say, a sweater? I realize this might be a silly question, but still what would be your rough estimate? If you had to break it up into swatching, working out the math, and writing the pattern, etc (without sample-knitting) in terms of hours spent at each stage?

This is a tough question to answer, but it’s an important one. I actually kept track of the Carlina pullover timing, so I’ll dig into that specific example, as I think it’s probably an average garment in terms of the time it took.

Idea generation: this would include swatching, sketching, etc: 3-4 hours

Grading Math: 5 hours in Excel

Pattern writing (taking my math in Excel, and putting it into a word document pattern): 3 hours

Proofing written word doc: 1.5 hours

Tech editing: Approx 2 hours (this wasn’t done by me, and was hired by Harrisville at $35/hr)

Photography: I think I probably spent 2 hours photographing this pattern, though it’s hard to accurately say because I photographed it with other patterns.

Photography edit: Probably another hour or so?

Layout in inDesign: 3 hours, which includes creating the sweater schematic, charts, etc.

Proofing of inDesign pattern: 1 hour

Uploading pattern to Ravelry: 0.5 hour

This is a total of 20-21 hours of my labor, which doesn’t include sample knitting. This sweater took me approx 40 hours to sample knit. Not an awesome return on my labor if I get my average amount of downloads, with the pattern selling at $7.5-8!

B from Thread and Ladle did an awesome survey of designers last year on time it takes to create a pattern, and if you haven’t seen that definitely check it out!

Do you knit the samples yourself?

I knit samples myself, and also use sample knitters. I’m designing about 20 garments a year (yikes) and my wrists can’t take knitting all of them. I knit most of the accessories myself.

What would you say is a fair compensation for sample-knitting?

Sample knitting wage standards are pretty horrible. The most common range I’ve encountered for sample knitting is anywhere between $0.11-0.17/yd, which in many cases even for the fastest knitter, wouldn’t net minimum wage for a sample knitter’s time. We’ve bumped our range at Harrisville anywhere between $0.22-0.26, and I can admit that’s still not a wonderful hourly wage. I’d really like it if eventually, the standard for knitwear pattern pricing could accomodate a much higher sample knit range. Sample knitting is much harder than knitting a pattern, as they are potentially catching problems in a design, and have to think more critically than basic knitting. I wish it were compensated more fairly.

Based on your experience, how do companies (publications, yarn companies, etc) generally decide on their compensation systems? For example, some pay a design fee and require exclusive rights to the design for a certain amount of time while others don’t pay anything upfront, but the designer gets to hold all the rights to the design.

I think this is largely decided by whoever started the company, or whoever is doing the bookkeeping for the company. This is probably something that seems trivial, but it can be a lot of labor for a company to calculate royalties quarterly, if they work with a lot of designers, and I think the accounting situation at a company possibly dictates the terms co-equally to the knitting direction. I think there are merits to either system, but it really just depends on the design, and how many royalties I might expect from the company, based on how many customers they have. I’ve encountered flat rates, a small royalty percentage in perpetuity, a high royalty percentage for a short amount of time, it all just depends on the company.

What advice would you give when it comes to working with yarn companies and magazines? What should a beginning designer pay attention to in contracts and agreements?

I think the biggest thing I’d keep in mind when working with a new company, with a contract that you’re unfamiliar with, is to fully, TOTALLY read the whole contract! I’ll be the first to raise my hand and say I haven’t done this in the past. Always know what you’re getting into, and ask questions if something seems unclear. Assume the contract is going to be enforced to the letter. The biggest thing, I think, to watch for is to confirm when payment will be issued after a pattern is delivered, and who is responsible for customer support if knitters have questions. Fielding customer support questions can, sometimes, take much more time (time you already are in the negative for, when calculating the full labor of the design!) so I’d recommend confirming with the company who is responsible for what, if it’s not outlined in the contract.

What would you suggest to someone starting with knitwear design: focus on getting published in magazines or focus on self-publishing?

This is so dependant upon the designers baseline personality, tough question to answer unilaterally. I think, for me, self publishing was never going to be a viable avenue, as I’m pretty camera shy, and I think that’s a component to successful self publishing. I think some—not all—designers who make a decent living wage from self publishing seem to be pretty comfortable in being the face of their company, and it’s something I’m personally quite bad at! That’s a broad statement though, and I know there are many fantastic designers who routinely self publish without doing this. I’d say, if a designer is just starting out, I’d try pursuing both, and weigh which is making you the happiest, while at the same time weighing which is financially viable.

I think this is also largely dependent on your skills, which I touch on in the next question. If you’re not a photographer, or don’t have the ability to lay out patterns, working with yarn companies and publications can be a huge help in alleviating the burden of that work, and is one of the major upsides to working with an outside company. You also don’t have to coordinate hiring a tech editor, which may have an upfront cost hurdle, as most tech editors will need to be paid before you’ve released a self-published pattern. It’s a complicated decision in choosing how you want to work and be published, and one that may not be answerable until you’ve tried both.

What skills (besides knitting and math) are essential to knitwear design?

Photography definitely helps, This is one of the hardest parts of knitwear design, or anything really, a good picture can sell an ok design, and a bad picture can hide a fantastic design.

I use Adobe’s creative suite for layout of all patterns. I use Illustrator to make charts and garment schematics, Lightroom to edit my photos, and inDesign to place photos and text together. Learning all three is undeniably helpful, though I know there are alternatives that others successfully use. Adobe’s creative suite is heinously expensive, and can be hard to learn without previous experience, all of which is a major barrier to getting into knitwear design. These are all factors to weigh when figuring out how you’ll release patterns, if you’re self publishing.

Marketing is a big one, and one I’ll confess to not being great at. I think a good eletter list filled with customers who love your design work can be helpful, too. I know once upon a time, Mailchimp had a free tier for people who don’t have thousands of e-letter subscribers, and because Instagram’s algorithm may mean not everyone sees your pattern launches, it can be a good second way of reaching out to people. This is also an area where working with an outside company can be super helpful, as they can do a lot of the marketing heavy lifting.

How can one tell if they have a talent for knitwear design? ...if they should continue pursuing this line of work?

I think there’s no definitive calculation for determining whether someone should pursue knitwear design. I think the hardest part of that calculation we’ve touched on a bit, in figuring out whether knitwear designers can make a wage they’re comfortable with, and still pay their bills. Aside from the financial side, I think the main thing in determining whether someone can do knitwear design really comes down to two things—ability to do the math, and ability to make patterns that your customers keep coming back to knit. The math part is easy to quantify, and the second part is definitely harder. I think finding a niche, and your voice, as a designer when creating patterns can be helpful (fully admitting that I sometimes don’t take my own advice…) some knitters like exclusively knitting colorwork patterns, and if you’re a colorwork designer, you have a chance of finding customers who will stick with you, wanting to knit the type of colorwork you’re designing.

As a knitwear designer, what lessons did you learn that you wish somebody had shared with you?

When I started out, I wish I had more information about the financial reality of being a knitwear designer, which is why I’m hopeful that talking more openly about these things will be helpful to other knitwear designers. When I first started out, I wasn’t sure if I was a totally crap designer, because I just wasn’t seeing the return I had hoped/expected when I published my first few patterns. This caused a lot of self-doubt in my ability. I started qualifying my self worth in terms of how many patterns I was selling, and that line of thinking can lead to damaging, unfair expectations on yourself. This can pretty easily poison your ability to generate new ideas, or cause you to start thinking about what’s likely to be “popular” vs what you love to design.

In the beginning, I wish I had set more personal boundaries for myself early on, so I had a better grasp on when I was stretching myself too thin. The freelance game can cause fear of ever saying no if an opportunity or idea comes around, because you never know when you’ll get another one. There are times where this can be a valid fear, but it’s less important than making sure you’re maintaining a healthy balance.

I also think setting personal ethics boundaries is pretty important to long-term happiness in this work. It’s a privilege to make financial decisions like this, especially when starting out, but I wish I had stopped designing with companies who only seem to work with white designers, use white models (who have also made no effort to enact future change), or pay their sample knitters an unfair wage, much earlier in my career (just as two examples). Staying true to yourself can be hard when it seems like work is hard to come by, and when it’s hard enough to make a living, but I do think drawing these lines when we can is a small cog in changing the industry for the better.

Think the last thing that I wish someone shared with me, treat sample knitting as WORK. It’s fun, undeniably the most fun part of designing, but it’s still work. If you wouldn’t be comfortable sitting at a computer for 6 hours without any stretching breaks, don’t do it when you’re knitting! If you can, set aside time for things that are fun, not related to knitting if possible. Maybe that’s crochet, music, drawing, or even knitting another designer’s patterns, whatever, but find something that’s not sample knitting to fill the time. This sounds probably pretty obvious, but take care of your body, and if you feel pain when knitting, stop. Deadlines are less important than your body’s health.

For me, the biggest obstacle in knitwear design is the fear of rejection. Have you had to deal with it much? How do/did you get over that? What advice would you give to get past this fear?

Rejection is apart of all proposal based work, and it’s one of the hardest parts. I definitely still fear rejection. In the journalism world, a lot of my proposals, job applications, photography has been torn to shreds, and though that’s given me a bit of rejection callus, I can’t pretend that it doesn’t sting when it happens. It’s not always possible, but I’ve tried to turn rejection into something productive when I can. I try and learn why something is being rejected, and attempt to build on it in the future. Maybe the company simply received too many stockinette designs, and they only wanted to publish one in a collection. Or, maybe they’d like to see a more detailed croquis, and because they were on a tight timeline, they decided to go with another proposal rather than asking you to submit something more detailed. It’s not always possible to quantify rejection with a “why” but when I can, it’s information I appreciate.

This will seem quite weird, but sometimes I like to disassociate my personal identity from my work when I’m submitting. If a design is rejected, no one is rejecting me, they’re only rejecting one idea I had. Because I’m a person capable of growth, I’ll have plenty more ideas.

Also entertaining the idea that whoever is rejecting me, may not be right, is helpful. This is such a subjective area, and I’m not submitting evidence based research for my engineering thesis, I’m designing a sweater. Some people like certain things that others don’t, and personal taste differences don’t mean I’m a bad designer.

Footnote, that I still feel down when I face rejection. Letting myself feel sad, in a lot of ways, can feel freeing: it’s a valid feeling.

Carlina Pullover by Whitney Hayward

Finding My Balance on Nauryz

Today, March 22, is an important holiday in Kazakh culture. It’s called Nauryz (meaning “new day”), and it coincides with the Spring Equinox. The holiday celebrates the balance between day and night, harmony in nature and our lives, the beginning of new year, and peace among people. Growing up in Kazakhstan, I loved this holiday as a kid because there were so many festivities and so much good food and everybody seemed happy on this day. As an adult, it’s the holiday that always kindles hope for more balance and harmony for me. This Nauryz, I realized balance and harmony are the very things I’ve been missing in my life lately. I decided to reclaim them by writing my reflections on things that have been causing me a lot of distress lately.

The conversations of racism in the knitting community that started in January of 2019 affected me deeply. As I read posts and heard stories, I felt instant recognition. I felt like what I have been missing in my time in the knitting community, what I could not quite put a finger on, was finally being talked about -- in a language that was new, scary and cathartic to me. Scary because people were hurt and accusations were made. But cathartic because it confirmed something I had been feeling for a long time but lacked the ability to articulate it.

When I was 30 years old, I left my entire life behind and moved to a different part of the world to be with the person I love. In Kazakhstan, I valued my independence, I earned enough to support my parents and brother, I had an established circle of friends. When I arrived to the US, I had to start my life all over. Because of my visa status, I couldn’t apply for jobs, my teaching certificate was not valid here, and, on top of that, we found out we were expecting a baby. In the search for a new identity in a new place, I picked up knitting as a way to keep my mind occupied. Later knitting turned into a life-saver as new motherhood left me completely lonely and isolated. Knitting kept me awake during night-time nursing sessions, and helped me keep my sanity as I held my babies upright throughout the night due to their severe reflux. During an extremely lonely period, I started sharing my creations online. The warm feedback and compliments from strangers helped me feel a little less lonesome.

As my work gained more attention, I started to sell my knitting designs to support my hobby. As my patterns began to sell slowly and consistently (bringing in a modest income), I started to wonder if I could make this a sustainable form of income as a stay-at-home mom. What I saw on social media led me to believe that I could give this a try. On Instagram, I noticed many stay-at-home moms who seemed to have turned their passions into sustainable businesses that let them support their families and give back to their communities.

So, I worked hard to learn knitwear design -- I took online classes, read books, and knit a lot. I noticed how successful designers used certain yarns, certain brands, certain products, and had relationships and friendships with key players in the industry. I tried to keep up with the latest trends in the knitting world, tried to foster connections, and tried knitting with patterns designed by successful designers to learn from them. But it seemed like I was missing something. My pattern sales didn’t reflect the growth in my skills.

On Instagram, the posts/Stories where I shared thoughts and feelings about being an immigrant and person of color in this country got the least engagement of all my posts. Some even unfollowed me right afterwards. Just recently, I mentioned Kazakhstan in my Instagram Stories and immediately lost followers. The patterns where I’m the one modeling designs get the least amount of sales. The feeling of being an outsider kept nagging at me. I couldn’t quite put my finger on it, but I thought it was just in my head as my husband (who is white) constantly tried to reassure me that people didn’t treat me differently here because I am Central Asian, an immigrant and have a different accent.

In these past few months, I started to pay attention to how little diversity I saw among the successful people in the knitwear design world. Before, I dismissed my own feelings of being an outsider, of not seeing anyone that looked like me held up as “success”, because I thought I was the only one who had these feelings. It was too easy for me to dismiss and erase my own feelings. When I visited Stitches Midwest and Vogue Knitting Live this past year, I was in awe of the diversity and creativity of the attendees. But this diversity was not reflected in the works that were featured by the vendors, in the displays, in the teaching staff, or publications. I also started to notice how white-washed my Instagram feed had become and how little diversity I saw in the feeds of the people/companies I was following and then emulating.

Since January, big-name designers and companies started sharing how they’ll now try to be more open, inclusive, and transparent, while they then quickly moved on with their regular programming. It felt like business as usual for them. Other brands completely disregarded this subject. Social media started to feel like a big crevasse with people sharing the pain of injustice on one side and unaffected people continuing to push their patterns, yarns, and products on the other. I found myself falling into an abyss of confusion, sadness, and disappointment.

Because I felt it was important to add my voice and experience, I started to join the conversations of anti-racism and fostering inclusivity. That also led me to question my own integrity in working with people, products, and brands whose position on the matters of inclusivity were vague, which seemed to show their indifference. Some well-established figures in the knitting world started following my account and one prominent publication reached out with words of sympathy and a vague promise on collaboration in the future. Given that they never showed interest before or after this message, this felt like maybe they were paying lip-service in the hopes I wouldn’t speak out against them. A few designers and small companies I had previously established relationships with seemed to distance themselves from me (ignoring my direct messages and a drop in their engagement with me on social media). I couldn’t help but wonder, are they uncomfortable with my recent involvement in anti-racism conversations? Should I have just stayed silent and played it safe? If I had, would they still be communicating with me now? The message I took away was that I should not talk openly about the problems within the community for the fear of losing existing relationships, collaborations, and contracts; and for the fear of ever securing any future ones.

Feeling worried and confused, I reached out to a well-known figure in the knitting world who has been a big advocate for BIPOC/POC representation. She didn’t hesitate to help me navigate a tricky situation with a yarn company that I was collaborating with. The company had stopped answering important emails pertaining to our collaborative project, and their engagement with my IG account suddenly dropped, which left me concerned that the company might be against addressing the issues of racism and that they didn’t want me speaking up about it either. Thanks to the encouragement from this ally, I got enough courage to write to this company about their behavior. It turned out to be a series of unfortunate timing coincidences, but they reassured me they were on the side of inclusivity. But, to be honest, that intent did not come through in their initial, brief generic statements on Instagram, and the business-as-usual promotional content on their feed and nothing on their website.

Just recently, one of my designs got accepted by a publication that has never featured a non-white model or a designer. I was initially so excited thinking, “Finally, I’m good enough to be accepted!” But this excitement quickly wore off because of our interactions after that. There was a serious delay with sending the contract and their “take it or leave it” response to my request for extending their extremely tight deadline (due to the delay they themselves caused) left me wondering whether they really valued me as a designer or I was merely a token minority they felt obligated to include. I wondered, do they treat all their designers this way or was their business conduct an expression of how much they undervalue me as a designer of color?

I am disappointed that the notion of “inclusivity” is commoditized in this way. As a knitwear designer who’s just starting to see the “behind the scenes” of the industry, I'm disappointed that once my design submissions get accepted, the deadlines and deliverables they expect are unrealistic, bordering on disrespectful. The time allotments for designing and knitting a sample(s) are simply untenable for designers who are either stay-at-home-parents or full-time working folks, who do knitwear design as a side hustle. Design commission payments I’ve received show me it can never become a sole income source, unless I publish an insane amount of patterns (a new design every week) or teach at many big profile fiber events. To teach at a fiber event (according to Clara Parks), a typical contract states that instructors cover the costs of travel/lodging and be responsible for filling the classes as the payment system is based on the number of students taught. Although, they may offer a stipend to partially cover the costs, to qualify for this stipend, one needs to teach 3-6 hours a day, which is often unlikely as organizers do not trust new teachers to schedule that many hours of classes per day. Clara noted herself how exploitative, though common, these contracts are, leaving newbie teachers in debt after teaching an event.

As for local yarn stores, I have visited and purchased from 4-5 that are near to where I live (Albany, NY). Although the interactions have been polite and courteous, I notice how their tone changes immediately when I inquire about possible teaching opportunities there (smile disappears from their face, and they find an excuse to end the conversation abruptly). The last one I visited told me the owner doesn’t hire anybody because she teaches all the classes herself. Quite accidentally, I overheard one of the ladies at my local Knit Night (where I’m the only person of color) share that she had been invited to teach classes at that same store. My heart sank, but I tried to brush it off thinking it’s probably an unfortunate coincidence. Is it though, or is it because as a young, Asian immigrant, I look so different from their clientele that I get automatically rebuffed? Instances like this keep happening, and I’m starting to doubt these are merely coincidences.

No one says this outright, but it seems that whenever I bring up feelings of being “other” in my Instagram account, I end up alienating my followers. I lose followers, engagement drops and sales do not happen (compared to posts where I do not mention those topics). It almost as if the knitting community does not want knitting accounts to talk about politics, identity or belonging; they prefer pretty pictures of knitting. I would love to be able to do that, too. I wish could turn off my feelings of being an outsider, but, as a person of color, I do not have that privilege. I cannot avoid being who I am or keep erasing myself for the comfort of others. I do not want to be an activist, but I do not want to be erased either.

Last week, my husband and I had yet another conversation about my place and my future in knitwear design, and I finally had to face the hard truth that I don’t think I can make a career out of this because the industry feels like a rigged game. In Becoming, Michelle Obama shares that in the nonprofit world, only privileged people can afford staying in the field because that type of work doesn’t guarantee steady income. It’s usually white folks who dominate this field because they have support systems to help them (family, connections, financial support, inheritance, etc). The knitwear design world seems similar to what she’s describing, which is why I don’t see much diversity here either. I can’t afford to keep investing my time, energy, and money in an area that seems to have no space for my full self.

Perhaps once my sons start school next year, I’ll look a for a day job and scale back on designing. Realizing this is an option for me has taken the pressure off trying to succeed in this field, which in turn is allowing me to show my true self, focus on what’s important to me and speak my truth. I’ll make whatever time I have left as a knitwear designer count and will do my best to work with people and businesses who are dedicated to fostering inclusivity. With more opportunities for honest communication and feedback, maybe we’ll reach the point when people and businesses will know what true inclusivity (acceptance, respect, transparency, trust, equity) looks/feels like and will strive to foster it in their businesses. If anything, this kind person who extended her helping hand to me during the moments of utter frustration kindled a hope that there are people who are genuinely invested in transforming this community to an inclusive one, the kind I hope to be a part of.