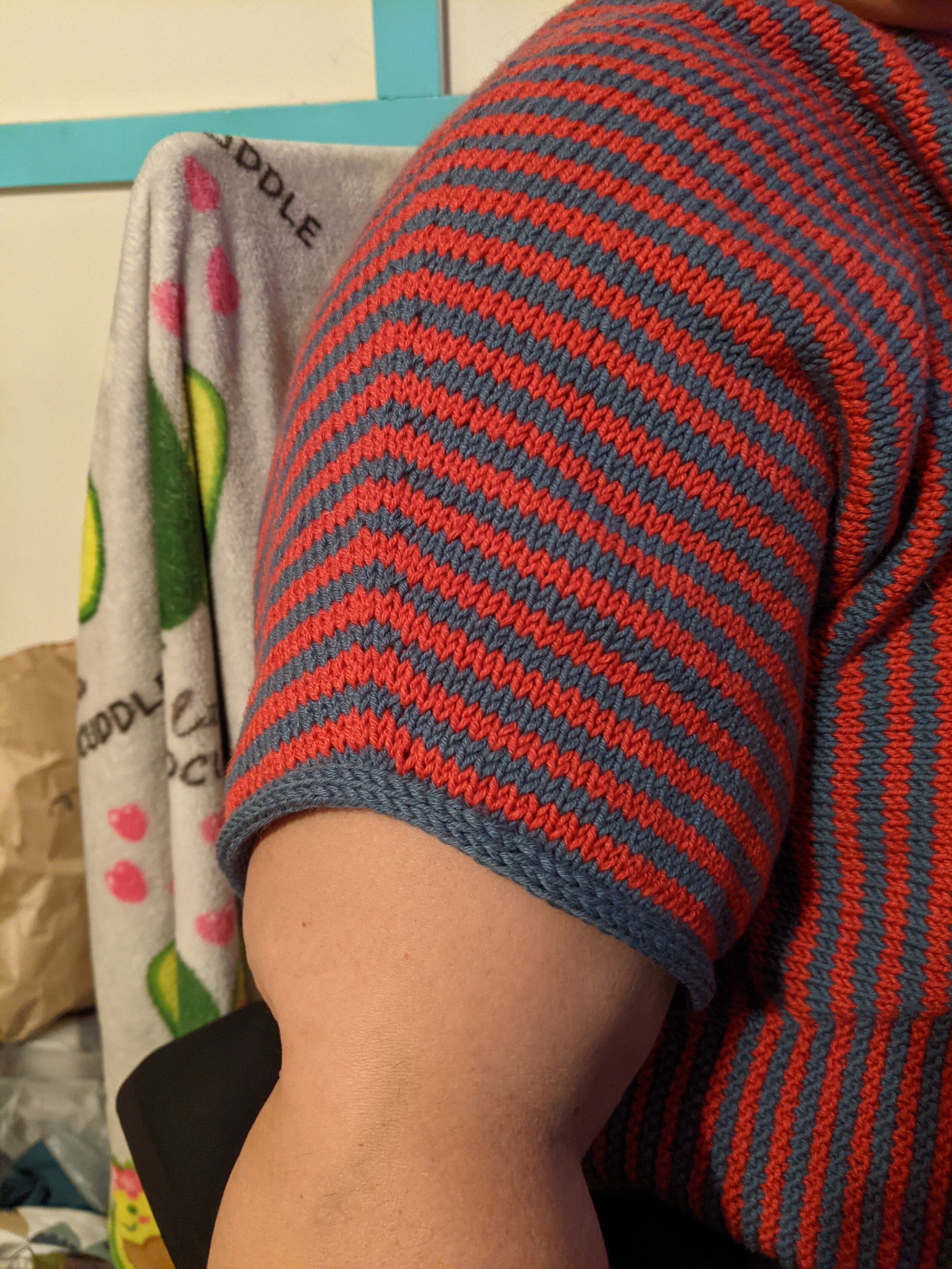

A multi-color version of Petunia Pullover, a sideways knit sweater designed by Ainur Berkimbayeva for Purl Soho

Read MoreCashmere People Yarns (Interview with Casey Ryder)

Hi Casey! I’m glad for the opportunity to chat with you about Cashmere People Yarns - thank you for taking the time from your busy schedule! I’m very fascinated by Cashmere People Yarns, so please excuse my extreme nosiness LOL! So, how did Cashmere People Yarns begin?

Cashmere People Yarns began back in 2009 with a four-year grant from the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), based in Rome, Italy. The goal was to improve the production and processing of high-value animal fibers and train local women to spin export quality yarns for the international market. The grant money was used to train farmers and provide the tools to comb their goats instead of shear them, resulting in fewer guard hairs. These fibers were purchased at a rate more than four times greater than the farmers would have received from the Chinese market. The funds were also used to establish eight spinning groups - three in northern Tajikistan, four in southern Tajikistan, and one in Afghanistan. Each group was outfitted with a workshops space, electric spinning wheels, and training. That first four-year grant was a success, and the project was awarded another four-year grant.

Training in spinning. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

Training in spinning in Markhamat village. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

How many people currently work for Cashmere People Yarns?

There are around 70-80 women employed within Cashmere People Yarns. Although each workshop space has a group leader, they make decisions as a group, including pay rates and pricing. Each woman has a key to the workshop space, so they are able to choose how much they work. Some have other jobs. They all have household responsibilities as mothers and (for many) heads of the household while their husbands live and work in Russia. About 40% of Tajikistan’s GDP is from remittances - husbands sending money home to their families, mainly from Russia. Many of the women in the north work on apricot farms in the summer. And the women in both the north and south have their own farms to tend to spring through fall.

I am their only distributor. And I wholesale to a little over 20 shops around the US and one shop in New Zealand.

Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

It feels like you have a good relationship with the people at Cashmere People Yarns. I noticed recently you were running a fundraiser to help pay one of the spinners’ medical bills. Do you do these kinds of campaigns often?

I don’t run these campaigns too often. This is the second such fundraiser I’ve done. The first was to support them in their fiber purchase the second year I was working with them. We all want the business to be able to support the needs of the spinners and their families sustainably, but it has been slow to “take off.” It’s definitely been a learning curve for all of us… finding the right amount of yarn to make at the beginning and scaling up from there… that first number was hard to determine, and I think they just did what made financial sense with the grant money. But then adding in my role as the wholesale distributor, a role I had no previous experience in… well, it’s taken some time, but I think we’re on the right track!

I was able to travel there in 2017 for two weeks and got to meet most of the spinners. We drank a lot of tea, ate a lot of food, and danced together. Even though I had limited conversations (I don’t speak Russian or Tajik, or Uzbek), that time with them was really special. I felt so welcomed, and they were all so eager to share their time and hopes for their work. I hope to visit them again. But it really solidified in my mind and heart the importance of what they are doing for themselves and their families. It’s huge.

I love reading about Cashmere People Yarns spinners and learning more about them, their values, and what working for the cooperative means to them. It sounds like spinning for Cashmere People Yarns provides a significant income for the spinners’ households. I’m curious, how much do the hand-spinners make moneywise, say dollars per skein? What does this mean in terms of an hourly wage, and how does it compare to the living costs in the region?

Tajikistan is a very poor country. Its GDP ranks 149th out of 195 countries. Afghanistan’s GDP ranks 177th. The annual average household income per capita in Tajikistan is estimated to be around $810 for 2021.

The spinners are paid per meter based on the quality of their spinning. They have developed a rubric of sorts for examining each skein and determining the pay scale based on the quality and consistency of the yarn.

On average, spinners are paid between $25-$120 per month when they are spinning. It varies from spinner to spinner, depending on how often they are able to come into the workshop, but the average is $70 per month. Some spinners choose to work from home, too, especially during COVID. But working in the workshop space is meaningful to them outside of earning income for their families.

Profit sharing day. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

I know producing yarn costs a lot, and Cashmere People Yarns are unique because all the yarns are handspun. So, how does this translate into the price and also your employees’ income? For example, let’s take the price of one skein of Cashgora ($48). What percentage of it goes to pay the hand-spinner? And where does the rest go?

I pay Cashmere People Yarns $17 per skein, which is 35% of the retail price. They then use this money to pay the spinners and re-invest in their business - purchasing fiber, paying for processing, buying dyes, etc. I wholesale cashgora for $26.40 per skein, which is 45% off the retail price. The profits I make go back into my business. I don’t calculate the cost of the time I spend promoting their business, reaching out to potential wholesalers, working with designers, storing the yarn, or going to shows on their behalf. That’s all just all rolled into my work with PortFiber.

Each skein is spun so meticulously, and as a hand spinner myself, I’m amazed at the evenness and consistency! Do the spinners receive training or do only skilled spinners get employed?

I wasn’t involved with the training. Shahlo was (is) the head trainer over those eight years of being supported by grant money. (She is currently in Russia receiving treatment for breast cancer.) Each group has a leader who is responsible for maintaining a certain quality of yarn. Shahlo trained the group leaders. There are spinners in the groups who have not been able to spin an export-quality cashgora but use the workshop spaces to spin local wools to be sold in the local markets. Once a spinner can spin well with the wool, they can try their hand at the cashgora.

Some of the spinners did have experience spinning on drop spindles or hand-made crank wheels, kind of like a great wheel, but smaller. But the electric wheels are so much more efficient and not as hard on the body.

Drop-spindling. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

Spinning with a hand-crank spinning wheel. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

Could you please describe the process a bit more: from sheep to skein? Does the fiber get dyed before or after spinning?

The goats are raised in the Pamir Mountains in the southern part of Tajikistan. They are small flocks that belong to families, maybe 10-12 animals. The animals spend the warm months all together in mountain pastures. Families take turns tending to the larger flocks.

Pamir Mountains. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

Rokhzora with her goats. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

Around March, the goats are combed, and the fiber is collected and sold to the Cashmere People Yarns fiber buyer. (I can’t remember his name!) He goes around to the different villages, examines the fiber from the farmers, and pays them for it. All of the collected fiber is sorted into natural brown and natural white and then gets shipped to Herat, Afghanistan, to be dehaired. Even though the fiber is hand-combed, there are still guard hairs in there - you can’t avoid them all. These would make for a prickly yarn, so it is sent away to be dehaired at a facility that has been doing that for decades. The dehaired fiber is then sent back to Tajikistan and dispersed amongst the spinning groups there.

Combing cashgora. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

Buying cashgora. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

Cashgora before dehairing. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

Spinners in Andarob village (Pamir). Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

The undyed fiber is spun and plied on electric wheels that were made by a man in Northern Tajikistan. Each bobbin can hold up to a kilo of yarn! They are some honkin’ big bobbins! The skeins are wound up on hand crank skein winders into 100g skeins. As each skein is handspun, the yardage varies from skein to skein.

There are three hand-dyers in the North - the three are group leaders there: Shahlo, Oygul, and Tulakhon. They dye the skeins in small batches on their stoves using acid dyes from the States (I’ve shipped them some) and from Turkey. The color palette is gorgeous. Some of the skeins start out a natural white and some a natural brown, so there is really a lovely depth to the colors. Each skein is tagged with a picture of the woman who spun it, the name of the color, and the yardage/meterage, and they are shipped to me in Portland.

Spinners in Andarob village. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

Spinners in Markhamat village. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

Spinners in Oshoba village. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

Workshop in the Pamirs. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

With the situation in Afghanistan, what is happening with the cooperative members in that region?

I’m getting mixed messages. There is a group leader for one of the spinning groups in southern Tajikistan that I am in touch with, and she says everyone is doing fine. But another person I work with says that they are afraid and wary of communicating that fear. I don’t have any direct contacts in Afghanistan.

Afghan spinners. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

I hope they are okay.

Have you traveled to that region? Does working with Cashmere People require a lot of traveling for you?

I haven’t traveled internationally, other than that initial visit to Tajikistan, which was paid for with grant money. I do travel for retail and wholesale trade shows and would love to do more of that in the future.

Does working with Cashmere People require a lot of work on your part?

It is a whole job in and of itself, one that I would like to dedicate more time to. I’m in the process of figuring out how to responsibly hire someone to help me in my shop so that I have more time to focus on growing Cashmere People Yarns.

What does the future hold for Cashmere People Yarns? What are your plans and hopes for it?

My hope is that I am able to scale up to a point where I don’t really have a lot of backstock. I want to sell all of what they ship me or at least most of it. There is only a limited quantity - part of the whole project is focused on sustainable agriculture. They are not going to breed more and more goats because it would not be good for the land. So there is a finite yearly quantity. Granted, there is still fiber being sent to the Chinese market, so there is perhaps a little room for growth. However, that infinite, Capitalistic growth model is not the goal here. With that in mind, and just knowing how obsessed we all are with great yarn, it seems feasible to sell out of a given year’s production.

Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

I’d love to be able to reinvest profits into Cashmere People Yarns. Or help to fund other projects within the spinning groups and farming communities.

I want this yarn in the hands of makers who get it, who understand how special it is, and who get hooked on working with some of the best stuff out there! I honestly think it is underpriced, given it is handspun cashgora, and it directly impacts women in developing countries! I sometimes want to reach through my computer, hold onto a shop owner's shoulders and say, “Just get it for your shop!” I mean, especially if they are already selling cashmere or other pricey yarns that AREN’T handspun by women in developing countries!

Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

I have a Dream Team Google Doc where I have a list of shops that I’d love to see stock Cashmere People Yarns, plus a list of designers, other yarn producers, and publications I’d love to partner with. This is where I go when I sit down to do what, in my mind, I refer to as “cold calls,” which really is just emails because who wants to talk on the phone these days?! I seek out shops that carry local yarns and indie-dyed yarns because I automatically know they value a smaller, (probably) more sustainable production scale. It’s been difficult not being able to go to shows and have people just touch the yarn. All you have to do is touch it to know it’s some good, good stuff!

In Tajikistan, they are working on building a fiber processing facility of their own. I think it’s still a ways away from being complete, but that will hopefully add more income opportunities for folks and cut down on some of the production costs.

They are also starting to spin and dye cotton, which is grown in northern Tajikistan!

I would love to be able to visit them again. And dance with them and drink tea together and share more of their story with the fiber community at large!

Spinning group leader, Barvoz village, Pamir. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

Woman with goats, Pamir. Photo by Liba Brent (shared with permission by Casey Ryder)

Thank you again, Casey, for this interview and for sharing the story of Cashmere People Yarns!

If anybody reading this blog post would love to check out Cashmere People Yarns, please visit www.CashmerePeopleYarns.com and @CashmerePeopleYarns on Instagram. Also, take a look at this collection of patterns featuring Cashmere People Yarns on Ravelry.

In collaboration with Casey, I designed a sweater pattern with Cashgora Sport yarn. The sweater design is called Rhythm and Rhyme, and it’s available both on my website and my Ravelry store.

Princess Leia's Knitted Wig

Make your own knitted wig to complete your Princess Leia outfit for Halloween!

Read MorePYRAMIS PATTERN'S TEST-KNITTERS

Melissa’s Pyramis

Size 3 on 37”/94cm bust and 42.75”/109cm hip

Yarn: Premier Cotton Fair - it is soft, drapey, heavy, but it stretched out after a few wears.

Yardage: 1100 yards/1005 meters

Modification: Added 2 inches (20 extra sts)

Notes: May make a smaller size next time.

Finished measurements: Hip - 43”/109cm (became 46”/117cm after a few wears), chest - 59.5”/151cm (became 58”/147cm after wear). body length - 23”/58.5cm

Click here for Melissa’s Ravelry project page. She is also on Instagram at MisLisKnits.

Catherine’s Pyramis

Size 1 on 36.5”/93cm bust and 36”/91.5cm hip

Yarn: Purple color is Classic Elite Telluride - 82/12/6 percent alpaca/linen/Donegal

Green color is Universal Yarn Wool Pop - 50/35/15 percent bamboo/superwash wool/polyamide

Yardage: 330 yards/302 meters of each color

Modifications: She knitted it with a looser gauge (17.5 sts x 34 rows), so the finished top turned out bigger. Also, Catherine knitted three rounds of 1x1 twisted rib all in purple color.

Finished measurements: Hip - 40”/102cm, chest - 48”/123cm, body length - 18.5”/47cm.

Click here for Catherine’s Ravelry project page. She is also on Instagram at Catherine_this_life

Olha’s Pyramis

Size 2 on 35.75”/91cm bust and 37.5”/95cm hip

Yarn: Luxury Selection (90/10 cotton/silk) and Silvedd Filati (100% silk). These yarns are drapey, so the top’s hip stretched out.

Yardage: 470 yards/430 meters of grey and 427 yards/390 meters of rose

Modification: worked the neck’s I-Cord with smaller needles

Finished measurements: Hip - 46.5”/118cm, chest - 53.5”/136cm, body length - 19.75”/50cm.

Click here to see Olha’s Ravelry project page. She is also on Instagram at Olhareva

Anne’s Pyramis

Size 1 on 34.25”/87cm bust and 37”/94cm hip

Yarn: Noro Silk Garden Sock, Grignasco Champagne

Yardage: 220 yards/201 meters of each yarn

Modifications: none

Finished measurements: Hip - 37½”/95.5cm, chest - 51½”/131cm

Click here to see Anne’s Ravelry project page. She is also on Instagram at Anneswolle.

Kristina’s Pyramis

Size 5 on 47.75”/121cm bust and 47.25”/120cm hip

Yarn: Amy Butler Belle Organic DK from Rowan, 50/50 percent wool/cotton

Yardage: 1179 yards/1078 meters in the garment, the finished garment weighs 449g.

Modification: Added bust dart as suggested in the pattern

Notes: Gauge was spot on on the gauge swatch, but the garter stitch row gauge really stretches out in a large garment even if blocked smaller

Finished measurements: Hip - 53.5”/136cm initially, 56”/142cm after wear, chest - 67”/170cm initially, 63”/160cm after wear, and body length - 20.5”/52cm initially, 22”/56cm after wear

Click here to see Kristina’s Ravelry project page. She is also on Instagram at Spinnkrok.

Cesca’s Pyramis

Size 2 on 35.5”/90cm bust and 37.75”/96cm hip

Yarn: Juniper Moon Farm Patagonia Organic (Sport weight, 100% wool) and De Rerum Natura Ulysse (Sport weight, 100% wool)

Yardage: dark color - 458 yards/419 meters and light color - 466 yards/426 meters

Modification: added 3/4 sleeves, used provisional crochet cast-on to work a 3-needle-bind-off on the side seams and to have live sts for the armhole finishing

Finished measurements: Hip - 41.25”/105cm, chest - 49.5”/126cm, and body length 20.75”/52.5cm

Click here to see Cesca’s Ravelry project page. They are also on Instagram at FelixAguilarCrafts.

Melissa’s Cropped Pyramis

Size 4 on 42”/107cm bust and 46”/117cm hip

Yarn: Neighborhood Fiber Co's Capital Luxury Sport yarn (80/10/10 percent merino/cashmere/silk) - the yarn is smooth and soft with some drape.

Yardage: 434 yards/397 meters of the darker color and 462 yards/422 meters of the second, lighter color

Modification: added 2 rows of the second color at the side seams to continue the pattern, omitted the neck I-Cord

Notes: should only add a single row on one edge next time, so as to make one row of the second color, then add the second row with mattress stitch

Finished measurements: Hip - 54”/137cm, chest - 56”/142cm, and body length - 18”/46cm

Click here to see Melissa’s Ravelry project page. She is also on Instagram at MG.wears.things.

Beth’s Pyramis

Size 7 on 44”/112cm bust and 56”/142cm hip

Yarn: Cascade Yarns Anchor Bay - it has form without being too stiff.

Yardage: 1300 yards/1188 meters

Modifications: none

Notes: The top fits bigger than expected

Finished measurements: Hip - 65”/165cm, chest - 78”/198cm, and body length - 21”/53.5cm

Click here to see Beth’s Ravelry project page. She is also on Instagram at SchuffBeth.

Our DIY Wedding

Yesterday, Facebook reminded me that eight years ago, my husband and I celebrated our marriage with a small group of friends at our friends’ backyard here in East Greenbush, NY. Now looking back and looking through these photos, I’m awash with a lot of emotions. I thought now is a good time to revisit this day and share some memories with you all because I’m guessing you’re knitters (or craftists in general) yourselves and probably are also into DIY projects, which our wedding had plenty of.

A little backstory: Phil (my partner) and I dated for 2 years while I was in grad school in Albany, NY. After my studies were completed, I went back home to Kazakhstan (KZ) with plans to come back to the US to pursue a Ph.D. degree sometime in the future. As I loved my work and being home in KZ, I didn’t rush to return to the US, so Phil and I broke up after trying to continue our relationship long-distance for a year. After about 1.5 years of being apart (during this time, we still kept in touch as friends), we got together in London, where I was visiting for a professional development opportunity and Phil came to see me there. We got back together and five months later, Phil came to KZ with a ring. We started the long process of applying for a fiancée visa for me to be able to come back to the US, which took us a whole year! We got married two days after I landed in the US, at a local town hall, with a couple of friends as our witnesses. Btw, I was still very jet-lagged when we were saying our I-do’s! A month and a half later, we had this backyard wedding party to celebrate our marriage with our friends (who were mostly friends from Phil’s work).

Moving to the other side of the world, leaving my established life, family, and friends was very stressful for me (for Phil too, I guess). So, I directed all of that stress into DIY’ing this wedding party, which means I basically turned into a DIY Bridezilla! Anywhoo, I have no regrets, except that I wish we had our parents there (it was too complicated to fly my parents from KZ and Phil’s from Chicago).

Our friends’ backyard was perfect: big enough to put up a tent to fit about 30 people and with lots of mature trees to create that cozy “garden-party“ vibe. We were/are so grateful to them for hosting our party and helping with the set-up and clean-up. Speaking of set-up, we hung mason jars and handmade pompoms (made from the tissue paper I found in Phil’s apartment) from the big tree on the right. Inside the mason jars are battery-operated tealights, which looked magical as it got darker outside. Our friends lent us their Christmas string lights, which we hung on the inside of the tent.

I had hand-sculpted all the flowers for our wedding from air-dry polymer clay. I had previously taken classes to learn this craft just so I could make my bridal bouquet in advance so that it looked exactly the way I wanted it to look and also to keep it as a keepsake afterward. I took these classes and made my bouquet (photo on the left) in KZ while I was waiting for the fiancé visa paperwork to finalize. The centerpiece flowers (photo on the right) and the big rose on the birdcage for collecting cards (middle photo) were made after arriving in the US. Also, those bunnies you see in the photo on the left? I made them in KZ and stuck them in the package I had to send Phil with all my paperwork while we were applying for a fiance visa. So yeah, those poor bunnies also had their fair share of stressful journeying across the world and deserved a central seat at our party!

This is our photo gallery with photos from our childhoods and important moments together, one of which was meeting Tom Hanks in person in LA!!!

I love this photo of my brother and I. I remember my mom kept saying “Smile!“ and that was my best attempt :D

London Reunion 2012: this is when we got back together! Btw I LOVED that store-bought sweater I’m wearing here because it looked handmade and reminded of a similar sweater my mom knitted for me a while ago.

“Hugs and Kisses, from Mr. and Mrs.” - so cheesy, right? I LOVED it though! These are Hershey’s Hugs and Kisses (chocolate candies) that we put custom stickers on (ordered from Etsy) with that cheesy line and the wedding date. We put them inside these little jars that we decorated with tea-dyed fabric and raffia. You are probably sensing the whole rustic-vintage aesthetic we were going for.

The friends who hosted our party were into brewing their own beer at the time and they generously supplied us with this delicious, homemade beer!

Our wedding invitations looked like this. Well, not exactly, as this is one of the many ruined ones. The iron-on stickers that I had printed the text on were such a PIA to get to work properly, and I ended up ruining about a dozen of these napkins/handkerchiefs. The ones that worked well (i.e. with all the text transferred clearly and nothing burned) were hot-glued onto cardstock and put into brown envelopes with decorative enclosures. I have a few of those saved somewhere as keepsakes, but I can’t remember where I put them at the moment. (I’ll edit this post later to add a picture of one of those).

Btw I sewed these napkins in KZ while awaiting my fiancée visa. I had previously dyed the fabric (100% cotton) and the lace trim (also 100% cotton) with black tea to give it a bit of an aged, vintage look.

I created this wedding sign by distress-painting a wooden plaque and stenciling the signage on it.

Looking back and looking through these photos, I can’t help but laugh at how intense I got about creating all these DIY projects. Crafting has been a way I have dealt with stress and uncertainty since I can remember myself, so it only makes sense our wedding party had to be this way!

Flying Home Top Pattern Release and Test-Knitters' versions

Flying Home Top is finally ready for its release and I would like to take a moment to chat about the pattern itself, the amazing pattern testers, and their versions of this top.

First off, the top you see on the pattern cover page is Size 2 modeled by me (my upper bust is 33”/84cm and full bust is 35”/89cm). I have about 7.5”/19cm of positive ease around my full bust, but it doesn’t look like it, does it? It’s because the tucks get longer towards the center and each tuck gradually adds more ease to the front and creates an A-line shaping. The top is knitted sideways, with the front worked in two pieces sewn in the front center and the back is worked as one piece. The sides are seamed with mattress stitch.

The pattern includes notes about adjusting sizes for bigger cup sizes and adding length to the top in general or just the front by adding bust darts.

I knitted this sample with Seismic Yarn Cellular in Thai Ice colorway. This base is a 60/40 percent blend of organic cotton and linen. This yarn costs $28 per 100g skein, and I used 2 skeins of it, so it was $56 total, plus shipping. I loved knitting with this yarn as it was soft (for a linen blend yarn), round, dense, and drapey. I also liked that it’s not very slippery like the 100% linen yarns I have tried. It felt very much like knitting with cotton, but it is definitely drapier than pure cotton, and drapiness is what I was after for this design!

I also made a second sample using a more affordable yarn - Knit Picks’ Lindy Chain. The content is very similar to the previous yarn; it’s also a blend of cotton and linen, but there is much more linen here (70% linen and 30% cotton). Plus, the yarn has the chainette construction. While I was able to get the gauge and I love this Turmeric colorway (btw there’s a lot of colors to choose from), knitting with this yarn was a bit tricky. I kept snagging the individual strands of the yarn and had to be very attentive and careful, which meant my knitting slowed down significantly. Despite that, I think this is a great value for the price ($6.99 per 50g ball). I used 4 balls of this yarn, bringing the total yarn cost to $28, plus shipping.

Ok, now let me tell you about the amazing pattern testers and their Flying Home Tops!

1. Tara’s Flying Home Top

Tara used Knit Picks’ Lindy Chain in Urchin colorway. She knitted Size 5, and she’s wearing it with 4”/10cm of positive ease around her full bust. She didn’t make any modifications to the pattern, which was a great decision because the top looks fantastic on Tara! Click here for Tara’s project notes on Ravelry and here to see her Instagram feed chock-full of beautiful knits!

2. Anne’s Flying Home Top

Anne used her own Little Skein Pianta (this base is not available yet), a yarn base that is identical to Seismic Yarn Cellular. And, because she is an amazing yarn dyer herself, she dyed this gorgeous shade of pinkish-beige colorway called Apple Blossom. She knitted Size 3, and she’s wearing it with 6”/15cm of positive ease around her full bust. She didn’t make any modifications to the pattern either. You can find Anne’s project notes on Ravelry by clicking here. Be sure to check out her yarny Instagram feed!

3. Jasmin’s Flying Home Top

Jasmin used Tess Yarns Raw Silk, which is a 100% silk yarn. This is the Mango colorway and it totally lives up to its name! Jasmin knitted Size 4, and she’s wearing it with 6.75”/17cm of positive ease around her full bust. Because Jasmin’s stitch gauge was slightly different than the one in the pattern, she decided to adjust her stitch count to make sure she got the necessary length (because the top is knitted sideways). To see more of Jasmin’s knits, check out her fun, colorful Instagram pages here and here. Jasmin is also a host of the Knit More Girls podcast, a multi-generational knitting production.

4. Rachel’s Flying Home Top

Rachel used Knit Picks’ Lindy Chain in Turmeric and Conch colorways. She wanted to use up the leftover yarn balls from her stash and that’s how she came up with this fun way of color-blocking her top. She knitted Size 1 with no modifications, and she is wearing it with 3-4”/7.5-10cm of positive ease around her full bust. You can find Rachel’s project notes on Ravelry by following this link. Rachel also shares her knitting and sewing projects on her Instagram page.

5. Emily’s Flying Home Top

Emily knitted her top with Seismic Yarn Cellular in Dragongruit Punch colorway - isn’t it the perfect name for this color?! She knitted Size 2, and she’s wearing it with 8.5”/22cm of positive ease around her full bust. Emily wrote up lots of helpful notes on her project page on Ravelry - be sure to check it out! Emily also shares her knits and other makes on her Instagram page!

6. Julia’s Flying Home Top

Julia used a 100% viscose yarn with an output of 320 yards per 100grams. She enjoyed working with this yarn because it is soft and pleasant to wear in the summer, but the top stretched lengthwise quite a bit after washing. To get the correct gauge, Julia used needles one size bigger than recommended as she knits more tightly (she used US 4 / 3.5mm). She is wearing Size 1 with 7”/17.5cm of positive ease around her full bust. To see Julia’s project page on Ravelry, click here. To see more of her knits, check out her Instagram page here!

7. Josephine’s Flying Home Top

Josephine knitted this top while learning Portuguese knitting! If you’re not familiar with this method, read up on it here - it’s quite fascinating! Apparently, it is great for people who have arthritis or carpal tunnel syndrome as it involves minimal hand movement. Anyway, back to Josephine and her top: she used Seismic Yarn Cellular in Rhubarb colorway. She made Size 1 and she’s wearing it with about 5”/13cm of positive ease around her full bust. Josephine cast on both sides of the front at the same time, which I think is a terrific idea for keeping the gauge consistent and making sure both sides are symmetrical. However, she did not enjoy the Kitchener stitch in the front center and is planning to make another version of this top where she will work the front as one piece (rather than two pieces sewn in the middle). I think that’s a great idea to try out, but it will make all the pleats face in one direction instead of symmetrically radiating from the center front. I think it will still look beautiful, and if you can’t stand the Kitchener, it’s definitely a good modification to this design! By the way, click here to see Josephine’s project page on Ravelry and check out her Instagram page here (so many yummy pictures of food)!

8. Melissa’s Flying Home Top

Melissa knitted her top using Seismic Yarn Cellular in Evoo colorway - and I’m so in love with it! Melissa knitted Size 3, but because this was her first time working with a linen-blend yarn, getting the right gauge was difficult and the top turned out bigger than she expected. I think the top looks beautiful on Melissa - it has a beautiful loose/breezy vibe! Check out Melissa’s project page on Ravelry and check out her Instagram where Melissa shares all her knitting, sewing and cooking!

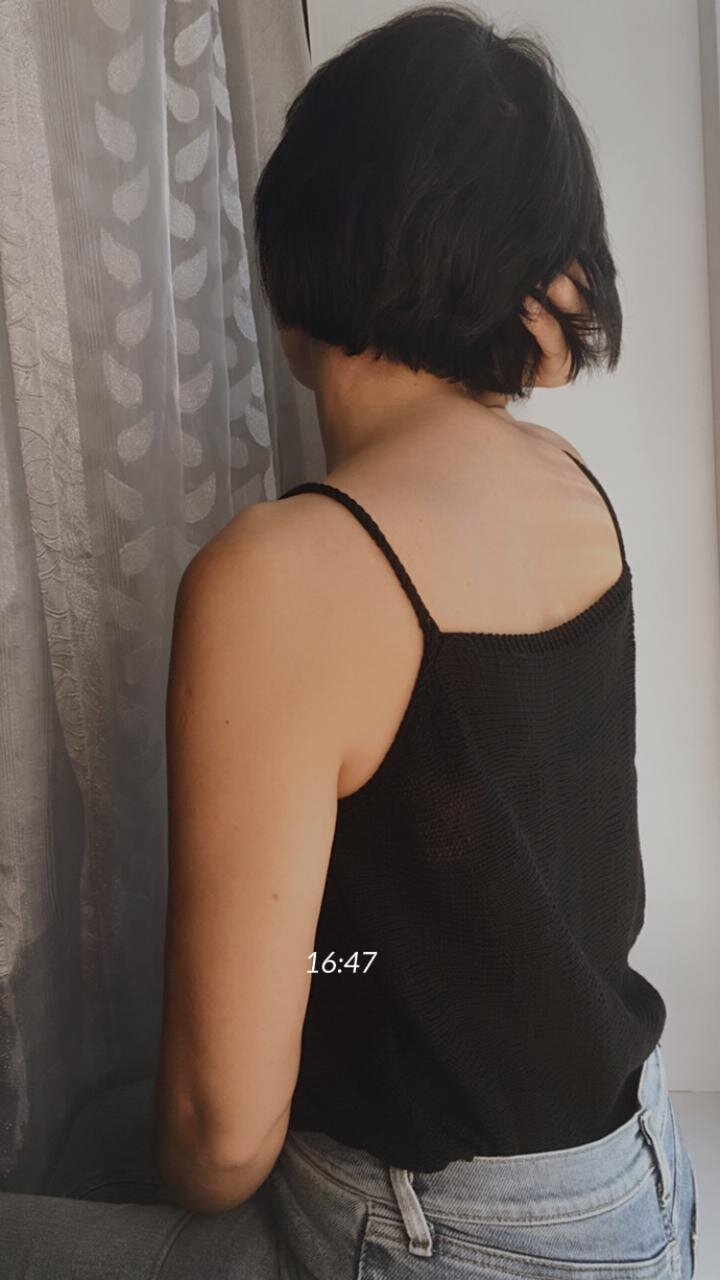

9. Kim’s Flying Home Top

Kim knitted her top using KPC Yarn Gossyp 4ply, a 100% organic cotton yarn, in Midnight colorway. She knitted Size 2 and she’s wearing it with 6.5”/17cm of positive ease around her full bust. Kim made the straps .5”/1cm longer than recommended, but her top and straps stretched more after wear, so she plans to make the straps shorter for her next top (she’s already knitting another Flying Home Top in a different color). Click here to see Kim’s project notes on Ravelry. Kim is also a knitting instructor based in Hong Kong, so if you’d like to book a lesson/workshop with her, check out her business page on Facebook!

PinDIY is a piracy website

Since I posted about PinDIY on my Instagram (the post is now archived), there has been a lot of information that was sent my way. I decided there should be a more permanent and easily accessible place for all that information to live, so this blog post is it. Please feel free to comment below with additional information and/or suggestions.

So, PinDIY dot com (I’m purposely not adding links to this website) is a website I came across quite by accident a couple of days ago. I noticed they are illegally selling my Laurel Leaf Pullover that I published through Purl Soho. I immediately contacted Purl Soho’s co-owner about this. She left a comment on PinDIY demanding the removal of the pattern from the website. Her comment was deleted immediately and there has been no other action taken by the website. The pullover pattern, along with several other of my patterns, is still there.

Upon researching more about this website, I found out that there are hundreds (if not thousands) of both knitting and crochet patterns that are being distributed illegally. There are even entire books that have been uploaded onto this site! How did they get all this digital content?! Several designers and I decided to compare our Ravelry sales reports to find the thieves (we were assuming it would be several people) but soon found out that the website actively encourages its users to upload stolen patterns onto the website by rewarding them with “coins”, the currency used on this website. This means hundreds and hundreds of people are involved in uploading their personal copies of patterns onto this site. In fact, on the website’s TOS/Rules page, the website admins blatantly say that they do not care about copyrights and theft, and any user who brings up anything about copyright infringements will immediately be blocked.

Things got worse as we learned more about this website. There are reports that PinDIY is spreading malware through the PDFs that they distribute, and when users open these PDFs, their computers get hacked and their personal information gets stolen. Bank account and credit card information are what they are after. Here is a YouTube video that explains how dangerous it is to download PDFs from piracy websites, like PinDIY.

Before discussing what we can do against this website, let’s take a look at what we found out about it on hostingchecker.com:

The website is hosted by: Alibaba.com LLC

WHOIS information: Click here

Organization name: ALICLOUD-US

IP address: 47.88.61.188

AS(autonomous system) number and organization: AS45102 Alibaba (US) Technology Co., Ltd.

AS name: CNNIC-ALIBABA-US-NET-AP

Reverse DNS of the IP:

City: San Mateo

Country: United States

Alibaba is a company based in China and it operates similarly to Amazon. PinDIY appears to be hosted by Alibaba’s US branch, so there is hope that we can get Alibaba to force PinDIY to either remove illegal content or shut the website down entirely.

Please do not use this information as an excuse to berate China and/or Chinese people. Thieves are everywhere regardless of geography, ethnicity, and nationality. I’ll be closely monitoring comments and will delete comments and/or block anyone who starts spewing xenophobic/racist rhetoric.

HERE ARE THINGS WE CAN DO

Designers/owners of stolen content

Report PinDIY to Alibaba

Here is the link for reporting copyright infringements. Btw this may take about 15-20 minutes, so it’s not something you can do on the go. Also, you need to be on your desktop computer as the form requires you to upload files.

Report PinDIY to Google

Here is the link for reporting (select Google Search). Reporting to Google will prevent the URLs with your patterns from showing up in Google Search. Obviously, this does not solve the problem entirely, but it can have a serious dent in the traffic this website receives.

File a DMCA (Claims of Copyright Infringement) with Apple

Click the link here to file a claim to get the PinDIY removed from Apple’s app store.

Report PinDIY to PayPal

PinDIY accepts payments through their PayPal address www.paypal.me/pindiy. You can report this account to PayPal by following this link and inform them of PinDIY’s illegal activity, which goes against PayPal’s Terms of Service.

Everyone

Report PinDIY app

Here is the link for reporting the app to Apple. (Fill out your info - be sure you read the bit at the top about how they use it). The next screen will ask for the URL of the app, it's: https://apps.apple.com/us/app/pindiy-crochet-knitting-works/id1560534288 Fill that in, then write a sentence or two saying what the problem is.)

Btw, the PinDIY app is active on Samsung and Android phones too, but it appears under the name Daohei. To report the app in the Google Play store on a Samsung or Android phone, there is a menu in the top right-hand corner with an option to Report as Inappropriate. You can select "Other" and type in the free text box: this app is selling stolen digital files without consent from their copyright owners and spreading malware.

Spread the word about how dangerous piracy websites like PinDIY are, especially the part about malware being spread through the PDFs this kind of sites/apps distribute.

WHAT ELSE CAN BE DONE?

Several designers are looking into the route of filing a class-action lawsuit. I don’t know how realistic this is, but I thought we could start preparing for it and gather information in advance just so we can move quickly if there is a chance at a lawsuit. I have created a form in order to make a list of designers/content owners who have been affected by PinDIY. I’ll keep this list private and only share it with lawyers if/when there is a chance of a class-action lawsuit. The form asks you for:

Your first and last name

Your email address where you can be contacted

Your location (city and country)

Links to where on PinDIY your patterns are being sold illegally

Links to where your patterns are sold legally (Ravelry, your website, etc)

Amount of loss (look at each pattern’s number of downloads and multiply that by the pattern’s price - do this for each pattern)

Btw fill this form even if your patterns are free. Most of us offer free patterns to drive traffic to our websites, blogs, and/or to advertise other patterns. I’m not sure what amount you should enter for loss; I’ll leave it up to you. If we get any advice from lawyers, we’ll contact you for additional information.

Designers in the UK! Please email Juliet of UK Handknitting at juliet@ukhandknitting.com. She has spoken with Action Fraud in the UK and will be filing a report.

PREVENTATIVE MEASURES

PDF stamping is something that can slow down the illegal distribution of digital content. While the stamped part of patterns can be cropped out, it still requires additional software to do that. Payhip offers this feature - click here to read about it. WaterWoo is a PDF-stamping plug-in that’s available for WooCommerce based websites. SendOwl offers PDF-stamping for Shopify-based websites. Unfortunately, Ravelry doesn’t offer this feature yet, so we should contact them and request this service.

Several designers have suggested adding a line saying “My patterns are available in such and such websites only“ within the pattern PDFs, so whoever accesses these PDFs can know if they got the pirated copy or an original. I think we can also add a line warning knitters/readers that if they downloaded/obtained their PDF elsewhere, it may contain viruses/malware.

Thank you everyone for sharing information and helping put together this blog post!

PS: HELPFUL RESOURCES:

www.stopfakes.gov (there is an IPR toolkit by countries)

JULY 14 UPDATE

Here is PinDIY contact info obtained via Apple (thank you Patty Lyons!) Patty has shared this text for us to email the developers:

I think you have intentionally violated my legal rights under 17 U.S.C. Section 101 et seq. and can be liable for statutory damage as high as $130,000 as set-forth in Sec. 504 (c)(2) of the Digital millennium copyright act (DMCA) therein. This message is official notification. I demand the elimination of the infringing materials described above. Please take note as a service provider, the Dmca demands you, to remove and/or terminate access to the infringing content upon receipt of this particular notice. In case you don't stop the use of the above mentioned infringing materials a lawsuit will be initiated against you. I do have a good belief that use of the copyrighted materials referenced above as presumably infringing is not authorized by the copyright proprietor, its agent, or the laws. I declare, under penalty of perjury, that the information in this letter is correct and that I am currently the legal copyright owner or am authorized to act on behalf of the owner of an exclusive… (include a link(s) to your patterns on PinDIY)

Patty suggests we email them all and email them non-stop!!! Also, Apple is looking into taking down PinDIY app! So, folks, all the reporting we have done seems to be making waves!

On a related note, Sarah Krentz, one of the many designers who has been affected by PinDIY, has been contacted on Ravelry by someone who used to be active on PinDIY. This person identified PinDIY’s owner as someone named Yiri Han (his email address is listed second to last in the PinDIY contact info above) and his assistant (who is an admin named Turqoise on the site) is a Turkish woman named Selnurd Denson.

July 29 UPDATE

Folks, I needed to step away from this problem for the past week because it has been too much to handle…

So far, the piracy website is still working, BUT their apps are gone from Apple and Google Play stores. It seems that they have changed their web-host from Alibaba Cloud (see the original post above) to Cloudflare, so now we need to send DMCA Takedown Notice to Cloudflare. Please see Miriam Felton’s blog post where she walks you through the reporting process step by step (see Part II of the post because Name Silo can’t really do anything as they are not the web host).

On a different note, this past Wednesday, I took a workshop with Kiffanie Stahle about copyrights and protecting our creative work from copycats, a slightly different issue than what we are dealing with here, but still, it was helpful in thinking about the most effective steps to take when it comes to copyright infringements and infringers. By the way, this article from Knitty explains the basics of copyrights and how they relate to knitting patterns and items knitted from patterns.

As indie knitwear/crochet designers, pursuing legal actions against copyright infringers is out of reach for most of us. While our work (knit/crochet patterns) is automatically copyrighted at the time of its publication/recording (btw Instagram/Facebook posts of our designs are also considered publications/recordings, apparently), we need to register our work with the US Copyright Office within the first three months of publication in order to reap the most benefits from the protections copyrights grant. That being said, it seems to be quite tricky to enforce US copyrights abroad, despite the USA being part of the Berne Convention, and it is impossible to do without having to hire a lawyer that’s local to the country where the infringement is occurring.

According to Stahle, the copyright laws have been written in the 80’ and had art galleries, big-time musicians, and artists in mind. But, a lot has changed since, and these laws do not address the needs of a lot of creatives nowadays (one has to prove significant financial loss in order to be able to bring a lawsuit in federal court). So, sometime soon (between 12.27.2021 and 6.25.2022), it will be possible to claim copyright infringements through Small Claims Court thanks to the CASE Act that was signed into law in 2020 (read more about it here). This will allow a more feasible/affordable way to pursue legal action against copyright infringement in the US.

But back to the piracy website… Right now, the most effective thing we can do is make sure their content does not show up on US-based platforms (btw DMCA Takedown Notices only work for US-based platforms). Google, Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, YouTube, etc all have reporting features where we can send the URL addresses and have that content taken down. With PinDIY, I’m still hopeful we can get Cloudflare to kick them off because Cloudflare is US-based.

By the way, we need to contact Ravelry about adding the pdf-stamping feature to the platform. That alone could resolve a lot of problems about the illegal distribution of patterns. On a related note, we need to be adding a line about the intended use of the patterns in the pattern listings. Things such as “for personal use only,” “do not distribute this file“, “not intended for selling finished items,“ “by purchasing this pattern, you are agreeing to these terms“ etc etc. I know lots of us already have such wording inside the documents, but it is a good idea to have that information within the pattern listings so potential customers do not have to wonder about these things. Plus, this information constitutes Terms of Service (or Contract) when it is available to customers prior to purchase. If people choose to distribute patterns illegally, then this is a whole other avenue for legal action (breach of TOS/contract).

On a personal note, I’ve come to realize pacing myself is really important as these kinds of problems eat away so much energy and time. I’m going to take some time this coming weekend to send DMCA notices to Cloudflare. Next weekend, I’m going to spend some time sending those URLs to Google (to stop them from showing up in Google Searches). The weekend after, I’m going to do a few more things related to this issue. Ignoring this problem won’t make it disappear, but neither will burning myself out trying to tackle this huge problem at once. I hope that whoever is reading this will do the same.

Fundraiser for a friend

Karin of The Periwinkle Sheep and I (Mama’s Teddy Bear) are running a fundraiser for our friend, a fiber artist, whose name we cannot disclose at the moment for safety reasons. They are going through a rough patch in their life and need our support to get back on their feet.

To help you understand the scale of support needed, they had to leave their home due to abuse and are now facing a custody battle for their child. They need help with rent, food, and essentials for their new home. Also, they need to replace all of the fiber, tools, and equipment so they can start working again.

How can you help?

Donate to our GoFundMe campaign

Buy yarn from our yarn destash

Buy yarn from The Periwinkle Sheep

Buy Ui Mitten Pattern on my website or on Ravelry

Buy Jili Socks Pattern on my website or on Ravelry

Participate in our auctions on @mamasteddybear_destash page

All proceeds (less shipping and transaction fees) from this fundraiser will go directly to our friend.

If you’d like to support this fundraiser but can’t spare any funds, you can help us by spreading the word about the fundraiser.

If you have some extra funds you’d like to donate, you can do so by going to either Ui Mittens Pattern or Jili Socks Pattern page and changing the price to an amount you’d like to donate (I have set the price as “Pay What You Want“ on my website starting from $5).

The fundraiser will run on January 6 - 13. We will announce the total amount raised by January 20.

Update:

Thank you everyone – you have helped us reach our fundraiser goal and surpass it! Together, we have raised $5328 in total for our friend in need. Thank you, from the bottom of our hearts for all your contributions. They will go a long way to help our friend. By the way, check out the pie chart below to see how this total amount was raised.

This has been amazing teamwork with Karin of The Periwinkle Sheep.

“You stepping into discomfort allows others to step into more ease.”

Couple days ago, one of the participants of the giveaway I hosted in my Instagram Stories shared this quote by Rachel Ricketts. I have not been able to stop thinking about it: it is so powerful. I think it captures the importance of individual action and personal accountability in antiracism work so perfectly.

With that in mind, here is a list of books, podcasts, movies, Instagram accounts, and other sources that were recommended to me, and I added several that I have found deeply influential in my understanding of the subject of racism. I plan to keep adding more, so if you have suggestions, please let me know.

Note: I did not include antiracism books that were written by white people as I have come to realize, thanks to Elle Glenise Pike of Where Change Started, how it is wrong that white people should profit off of antiracism work. There is a difference between becoming part of the solution and making a living through this work.

BOOKS:

So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo

How to Be Antiracist by Ibram Kendi

Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race by Reni Eddo-Lodge

Me and My White Supremacy by Layla F. Saad

Talking Up To the White Woman Aileen Moreton-Robinson

White Rage by Carol Anderson

We Want to Do More Than Survive by Bettina L. Love

What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker by Damon Young

WORKSHOPS (in person):

Undoing Racism Workshop: Antiracism training for anyone in Human Services, Education and beyond http://antiracistalliance.com

INSTAGRAM ACCOUNTS:

Note: When entering online spaces of the following people, please be respectful in how you interact with them.

@wherechangestarted – Inspiring individual action and personal accountability with self-guided educational resources for becoming antiracist

@aja.barber – Aja holds important conversations about fashion, trends, and sustainability through the lens of antiracism and intersectionality

@iamrachelricketts - Rich resourcses that articulate what structural racism is and how it fits into historical patterns that continue today

@theconsciouskid – Parenting and education through a critical race lens

@leesareneehall – Leesa facilitates workshop leaders in unpacking their biases in order to create inclusive learning spaces

@rachel.cargle – Thought-provoking, critical discourse on racism in the US

@dr.rosalesmeza – Helping women of color identify blocks, confront colonial mentality, and reclaim their intuition so they can live whole, well, and free

@alokvmenon – Transgender/gender non-conforming writer, performer, and speaker who focuses on expanding notions of femininity, issues of ableism of beauty standards, historical revisionism and cultural racism

@kanishka.sikri – Poet, writer, post-de-colonial theorist, transnational feminist

PODCASTS:

Stepping Into Truth: Conversations on race, gender, and social justice with Omkari Williams

Good Ancestor by Layla F. Saad

Decarcerated hosted by Marlon Peterson

Justice in America Podcast (The Appeal)

MOVIES:

When They See Us (Netflix miniseries, the after-show with the director, actors, and Oprah) – “a dense, fast-moving series that examines not just the effects of systemic racism but the effects of all sorts of disenfranchisement” The Guardian

WEBSITES:

http://www.dismantlingracism.org/

Interview with Sukrita Mahon: Pattern Pricing, Financial Accessibility and Inclusivity

Hi Sukrita! Thank you so much for agreeing to sit down and chat with me. I have long been admiring your outspokenness, your thoughts and incredible amount of work you have done to educate people on anti-racism, dismantling white supremacy, and fostering inclusivity in the knitting world.

I will be honest, your last couple posts on Instagram have initially made me uncomfortable, so I sat with my discomfort for a few days, after which I decided to ask you directly about my confusions.

1. With your recent posts, are you saying designers should undervalue and not charge their worth for their work so more people can afford knitting patterns?

No, not at all. Designers work is undervalued and it’s a deep, systemic problem. It's absolutely fair to say designers are not paid their worth. But the issues were around the kind of discussions that were happening, where white women were simply saying "increase your patterns by 100% and people will pay"... Which is extremely insensitive to those who can't afford it. The concerns about affordability are shrugged off in favour of apparently white people making more money! As usual, to be honest. Knitting is already a very insular community that isn't welcoming enough to lower income people. That was the point of my posts.

I would like to see the pricing discussion reflect the diverse customer base, not just focused on rich, white people yet again. That's all.

2. It sounds like you’re saying white = wealthy and non-white = low income. Do I understand you correctly? Could you expand on this a bit more?

I didn’t make up the disparity out of nothing, the evidence for median income according to race and gender is well-documented. This Wikipedia page is a good starting point, as is this census chart.

It should be noted though that the only reason Asian is on top is because Asian men earn significantly more than most people (due to education) -- Asian women still tend to earn less than White or Asian men. See this for reference.

Setting that aside, I’m only pointing out what it looks like to me, especially in the online community, and I know I’m not the only one who sees it. The average white crafter seems to think nothing of spending lots of money on a project bag, or hundreds of dollars on yarn for a single sweater. In most podcasts hosted by white people, the unstated assumption is that this is the norm -- which it is really not. Somehow, the loudest voices in the room end up being (or appearing) rich and white.

3. As for the pattern prices, to be honest, I was in support of the idea of raising prices for patterns, not by 100%, but maybe by 10-20% to better reflect the value of work that goes into publishing a pattern. I have increased the last couple patterns I published by half a dollar and a dollar respectively. I couldn’t imagine raising much higher than that. I agree with you that it’s a privilege to get to design, but I also have trouble with the push to keep pattern prices low even if it means many designers won’t be able to continue doing this work, especially lower income designers. The way I interpreted your words, please correct me if I am wrong, is that designers should get a second job or something so they can keep pattern prices low for people to be able to afford them. If not, they should just give up on designing. While I agree it’s a privilege to get to do what you love doing for a living, I’m wondering if you’re saying people shouldn’t pursue knitwear design as a valid career choice and a valid income source?

I'm not saying that at all. People are free to increase their prices, it's hard to make a living doing anything in fibre arts. You do what you have to do.

But I do have trouble with making spaces more exclusive than they already are. Of course, I support designers, but I have been seeing a lot of really entitled behaviour from white designers specifically.

I firmly believe that creative work should be valued much more than it is -- I am one of those underpaid fibre artists too. That’s why it’s doubly strange to see white people asking to be paid more, as if they’re the only ones struggling to make a living. There seems to be a severe lack of awareness and education around what it even means to be a crafter: its devaluation today has its roots firmly in colonialism and imperialism.

It is deeper than the conversation seems to want to allow space for.

4. So, you’re saying raising prices at the scope Hanna Lisa Haferkamp* suggested is sort of a “quick fix” that won’t do anything good to anyone? How do you envision knitwear designers getting fairly compensated for their work while keeping in mind there are many low income knitters who can’t afford buying patterns at these new prices? You’ve mentioned Aroha Knits and a few other designers trialing “pay what you can” idea... also you mentioned TinCanKnits free** patterns as an example.

My solution, as Aboubakar Fofana says, is impossible. If it’s true equality and fairness we want to achieve as crafters, then it will take a dismantling of systems well beyond the design world.

But we can start with being aware of the effect we have on the world around us.

Instead of seeking personal gain, we can try to build an alternative, inclusive environment that celebrates everything about what we do. I see our power in the ability to inspire each other, and that’s something we can keep doing regardless of our financial situation (hopefully).

Every business is unique and every designer’s vision for what is possible is unique to them. I look forward to seeing innovative ways of addressing the issue. What was possible for Tin Can Knits with their free patterns may not be possible for a one-person team; others may not want to try the ‘pay what you can’ model if they’re not confident in their customer base. Being honest with yourself about what you can do is really important.

5. What do you mean by “relinquishing privilege” when you ask that of designers? What does it look like?

Relinquishing privilege is directed (mainly) at white/middle class designers who have a lot of opportunities that others don't have. There are so many things they can be doing to make the community better and helping other people. I don't see them doing that, so to demand a price rise is absurd.

I don't think it applies to everyone, BIPOC designers have less privilege and I still see them/you doing so much for the community.

6. I saw a post on Instagram asking an interesting question of whether knitters are a community or a market. From what you have said, it sounds like you think it is (or should be) a community. Can’t it be a market at the same time? What considerations (ethical etc) should businesses keep in mind when marketing to knitters on Instagram?

Isn’t it both already?

White people love ethical consumption as long as it doesn’t involve thinking about people or the society we live in. You can’t have ethical businesses that are against inclusivity, or diversity. By focusing their marketing strategy on those who have the most money, businesses are actively being exclusive.

I think most makers know how to cater to the fibre market-community already. It’s an industry based on engagement with the community. I guess my main piece of advice would be to know who your customer base is, and why.

Thank you Sukrita*** for your thoughts. I really appreciate you taking time to explain all this.

* Hanna has since posted an update about switching to “Pay What You Can” pricing model.

**Free patterns are not really free. A lot of hours and resources go into them. Patterns are offered free for many reasons: mainly, to advertise other patterns, increasing customers’ trust and loyalty, to sell featured yarns, etc. If you enjoy the free patterns by your favorite designers, be sure to show your support and appreciation if and when you can.

***If you found this post valuable, you can buy coffee (Ko-Fi) for Sukrita following this link.

Test-knitting: why and how I do them

A couple weeks ago, a fellow designer Julie Robinson asked me a few questions about running test-knits and how I do them. I wrote up my answers as a blog post hoping it may be valuable for somebody else. I have been hesitant to publish this post as I am still not sure if I am doing it right from the perspectives of both valuing my test-knitters’ work and making sure I stay solvent when it comes to my knitwear design endeavor. I still feel conflicted about running test-knits, and I have been looking for ways to make it thoughtful, meaningful, and win-win for both my test-knitters and myself. For the sake of full disclosure, I would like to make it known that my pattern sales average at about $350 (550)* a month. This amount is just enough to cover my knitwear design expenses which include:

a) my tech-editors (average of $80 per design)

b) yarn for my new designs (both for self-publishing as well as making swatches for design submissions to knitwear magazines and yarn companies)

c) software (Adobe Creative Suite, which is $33 a month)

d) website ($144 annual fee)

e) equipment (such as computer, DSLR camera and lens, printer)

f) office expenses (printing paper, ink for printer)

g) shipping expenses (to ship KAL and giveaway prizes)

h) professional development (workshops and books on knitwear design)

I do not know if this amount is reflective of how much a relatively beginning level knitwear designer like me makes, but I have a feeling this amount is not at the very bottom.

So, what is test-knitting?

I think of test-knitting as beta testing of a new pattern. By the time I start a test-knit, I have my pattern checked several times by me and my tech-editor, and I’ve already made a sample. So, for me, test-knitting is the last step before publishing a pattern.

I know a lot of designers get their patterns tested first, tech-edited last. I used to do it that way too, but I noticed how stressful and frustrating it was for my testers then. Now, I get my patterns tech-edited first because I want to be sure the testers are working with the final version and have as smooth experience as possible. English is not my first language (not even second, or third), so I do not want to frustrate my testers with directions that are not clear enough or there may be some errors with numbers that I have not noticed.

Is test-knitting necessary?

Yes and no. In theory, if I’m using the sizing standards and grading the sizes correctly, and I have checked the instructions thoroughly and the pattern has been tech-edited, then there is no need for test-knitting. In fact, Amy Herzog (I attended her Ultimate Sweater workshop at VKL NYC) advises against test-knits (because of fair compensation issues) and recommends finding/hiring a highly detail-oriented tech-editor.

In reality though, after working on my patterns for so long, I reach a point where I stop seeing things, and my tech-editors often seem to miss a few things (they are human too), that my patterns still benefit a lot from being tested.

How does it work?

I send an announcement to my mail list sharing as much information as possible about an upcoming test-knit: a photo of the finished design, yarn, yardage, sizes, deadlines, and my expectations. Interested knitters respond, and we go from there. Most of the test-knitting discussions happen in my Ravelry group, where I create a separate thread for each test-knit. Some test-knits have to be kept secret due to the design being published elsewhere (not by me), so I share very generic information at first. When I get my test-knitting team assembled, I share all the rest of the information through Google Docs by invitation only.

Once a test-knit is completed, I add the final pattern to the testers’ Ravelry libraries and ask them for their choice of two patterns (self-published ones) from my Ravelry store. Also, to credit them for their work, I have been adding the test-knitters’ names and links to their Ravelry pages in the published patterns. As I know exposure is one of the reasons knitters sign up for test-knits, I try my best to give shoutouts to my test-knitters whenever possible on my Instagram account.

What makes a good test-knitter?

Every knitter who signs up for and finishes a test-knit is a good test-knitter in my books. That being said, there are certain aspects of test-knitting that I appreciate and look forward to in every test-knit. I do not expect every tester to meet these requirements, and oftentimes, with the variety of testers I get, pretty much all these aspects get covered in every test-knit I have conducted.

Gauge swatching. For me, one of the biggest reasons for running a test-knit is to check the fit of a garment or an accessory. Unfortunately, if a knitter does not take the time to check the gauge (and to check if his/her alternative yarn is suitable at this gauge), the result will not turn out the way it is intended, and the fit will not be accurate.

Being attentive to details. Sometimes, there are knitters who read a pattern, think they understood all the directions, and then rarely consult the pattern until they are done. What ends up happening is these knitters start filling information even if it is not there or interpreting directions differently based on their first reading. Unfortunately, these testers are not able to provide any feedback. I have heard from my detail-oriented test-knitters that they approach a pattern that is being tested as if they are beginner level knitters themselves. They say this perspective helps them spot problematic areas easier.

Timeliness. Deadlines are there for a reason, and I try to communicate this as clearly as possible. And, I try to set the test-knitting timeframes as realistic as possible, estimating for about 1-2 hours of knitting a day. I really appreciate the test-knitters who finish on time. I also appreciate when knitters reach out to let me know if they are struggling with meeting deadlines (unforeseeable things happen to all of us). What I do not like is when testers disappear after receiving a copy of the pattern. I get disappointed by these people and try to avoid those knitters in the future test-knits.

Communication. This is # 1 reason why I run test-knits. I love those testers who reach out with questions, comments, and suggestions as needed. I also love the testers who are able to communicate through their photography. And, I do not mean professional photography per se (though it’s wonderful if one can do that), but taking pictures so they can communicate how an item fits from different angles.

Do testers get compensated?

Generally, testers do not get compensated. Should they be compensated? It depends. As a knitter, the way I think about a test-knit is if I see a design that I’d like to knit, the timeline sounds reasonable, and the yarn is within my reach (either in my stash or within my budget), sure, why not test-knit? I’d be getting the pattern for free. Plus, I love giving feedback and helping someone out. And oftentimes, test-knits have the community aspect in them that they often feel like knit-alongs.

On the other hand, knitting takes a long time and providing feedback (for me, this is the most important part of test-knitting) means spending even more time and effort. Because I depend on this feedback as a designer, I want to show my gratitude in some tangible ways. Usually, my testers get the final copy of the pattern they are testing, plus two more patterns of their choice from my Ravelry store. There are also occasions when yarn companies I’m collaborating with offer discounts for my test-knitters, and this is helpful in making yarn a little more accessible and a test-knit more attractive. Sometimes when I have tighter deadlines and stricter requirements, I try to make up for this by offering yarn support, either full or partial. To qualify for yarn support, a knitter should have previously test-knitted at least two of my patterns.

How many testers do you usually get?

I try to get at least one person per size.

Do you have to find a tester for each size?

Ideally, yes, but I have a harder time finding testers for the bigger sizes (sizes after XL), which I recently started adding to my patterns. I still include the sizes that have not been tested (if I don’t manage to find testers) in the pattern because all the sizes are graded following the same grading and mathematical reasoning.

As a knitter, I feel more confident about starting a new sweater when I see its finished version in my size. So, this thinking makes me want to make sure all sizes get tested. However, sweaters take a long time and a lot of yarn to make, and the bigger the size, the more it takes to finish one. Moreover, Amy Herzog mentioned that one cannot fully rely on test-knitters’ feedback about the fit because we cannot see for ourselves if those knitters’ gauge is consistent throughout the project and what the exact finished measurements are. Because of these reasons, some designers (those who can afford) and most yarn companies hire sample knitters.

Sample knitters are different from test-knitters in that they get compensated for knitting a sample, but they do not get to keep it. The biggest difference between sample knitters and test-knitters is that the former is a contractor and has a strict set of rules to follow. Sample knitters receive yarn, and they get paid at an agreed upon rate. This rate varies at approximately 10 - 30 cents per yard (or meter) depending on the company and complexity of the required knitting. Sample knitters send the finished objects (FO) to the companies that hired them. These FOs are checked to make sure all the pattern directions have been followed and all the measurements are consistent with the pattern schematics before payments can be made.

In the ideal world, designers should make enough money to compensate for their test-knitters and be able to afford hiring sample knitters. The reality is many designers do not. How do we go about this then? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

*Usually, my monthly pattern sales range between $250 - 450, so $350 is more of an accurate estimate. However, during the year, I had a couple of blog features that spiked sales for two months of the year, thus skewing the average result.

Nightshades collection by Whitney Hayward

Interview with Whitney Hayward: knitwear design as a career

Hi Whitney! I’m so happy you agreed to sit down with me and chat about knitwear design and what goes on in the world of a talented designer like yourself.

Could you tell a bit about yourself, how you got into knitting and designing knitwear, and how you started working for Harrisville Designs?

Sure! How I got into knitting: I’ve been knitting since 2010, a skill I picked up from my host family when I was living in Japan for a language study in Nagoya. I was especially terrible at reading Japanese, and I wanted to better connect with my host mom Kazumi, who seemed to know how to do a little bit of everything. Once the weather started to get a bit cooler that year, she started knitting a scarf, and for whatever reason I thought that learning how to knit might help me with my feeble Japanese reading comprehension. It did, and I will never be able to say thank you enough to her for teaching me a skill I hope to use for the rest of my life. It was hard to learn how to read western patterns after learning how to read Japanese patterns, though! I love the way Japanese patterns are written in schematic form, vs fully written.

How I started designing knitwear: I continued knitting after leaving Japan, but definitely treated it as a fun hobby that I occasionally picked up, focusing more on journalism. I graduated from my university, and got a job at a mid-sized metro newspaper in Portland, Maine as a staff photojournalist. I loved, and still love, print journalism. I worked for an incredible photo editor, Yoon Byun, who I was lucky to learn from at an early age in my career. My photography would be much crappier if I hadn’t! Despite the best circumstances at the paper, a few years in, I started to feel myself change, both internally and externally. Fires, court, homicide, were all possible daily assignments, and the uncertainty of what the day would hold gnawed at me from the moment I woke up. The entire state of Maine was our coverage area, and I was driving close to 35,000 miles a year; my car felt like my home sometimes! This is when I started to knit voraciously, and would rarely be seen without my knitting, as I was absolutely using it as a coping mechanism. The downtime in the car, combined with the need for a mental distraction, was a perfect reason to non-stop knit. This eventually transitioned to me tinkering with designing out of curiosity, and self publishing a few designs, which, I can admit, did not go well if we’re judging by whether they made me any money! Despite that, I eventually met the people at Quince & Co., who are also based in Portland. At the time, I felt like I was hanging by a thread at the paper, and was incredibly fortunate that they were looking for a new in-house photographer, and someone to help out at Twig & Horn, their side knitting notions company. I quit journalism, and dove headfirst into the knitting industry, eventually starting Stone Wool with Quince. Leila and Dawn at Quince were so foundational to me learning how to be a better knitwear designer, and I’ll never be able to repay them enough for all of the knowledge they imparted.

After working at Quince for a few years, I started to desperately miss my family back home in Missouri. My partner has family who lives in Arkansas, and we decided to move back home so we’d be able to visit more often. I left T&H and Stone Wool in incredibly capable hands, and decided to give a try at going freelance. Harrisville yarns (frankly, all woolen spun yarns) are my favorite to knit with, and I reached out to Harrisville to see if they were looking for any freelance designers. I reached out to them at a serendipitous time, as they were looking for a designer to take on a new project they were calling Nightshades. We both felt happy with how the partnership worked with that collection, and that freelance work transitioned into a job at Harrisville as their pattern director.

“Knitwear design (hand-knits design) is not a job, but a hobby” seems to be the common thread among many knitters/designers. What are your thoughts about that? Is it realistic to make a living doing knitwear design?

Yes, I’ve heard this too. I absolutely think knitwear design can be a hobby, or part-time work, for designers—I think that’s a-ok! However, the idea that knitwear design is exclusively a hobby activity downplays the hard work required to make an accurate, well written pattern. It also illustrates a more troublesome part of designing, that many people (myself included) cannot make a full-time living from knitwear design alone.

I think there are two things underpinning this. One, the less serious one, is that most of us who decided to pursue knitwear design enjoy knitting. It’s natural to believe that knitwear design will be as fun and engaging as knitting. As you know, much of the actual work of pattern writing requires no knitting at all, rather math / spatial reasoning problem solving. Math is not a hobby for me, and I suppose most knitwear designers would fall under that camp. It’s hard work. Admittedly with not much quantifiable data to substantiate this belief, I think the perception of knitwear design as a hobby has influenced the average price of knitwear patterns, especially if you compare them to digital home sewing patterns.

The second, is that there’s a lot of veiled secrecy about what it’s like to pursue knitwear pattern design full-time, and what most people are making annually. I will pointedly say that I’ve never, ever, earned enough from royalties, publication rates, or self publishing to make a living wage when I’ve worked as a freelance knitwear designer. I’m individually responsible for funding my living expenses, rent, etc, and no way does my royalty-only money come close to meeting those bills. Anytime I’ve been fully freelance, I’ve always supplemented my income with photography assignments, freelance marketing/social media work, etc. Just to break this down a little bit, on average, around 30-50 people download each of my patterns, an average that accounts for some of my patterns that haven’t been so popular, and others that have been more popular than that range. Although I’m so grateful that one person wants to knit something I’ve made, and am worried this next bit will sound as if I’m scoffing at these download numbers, there’s no way I’m able to live on that income alone. Let’s say that a pattern gets 60 downloads, and the pattern is sold at $8/download. That’s $480, classified as self-employed 1099 income, which is taxed much higher than if I earned that $480 through an employer. Let’s then say that I could magically publish 1 garment pattern per week (which would be insane!)—I’d need to get those 60 downloads weekly, and assuming I’m trying to hit full-time at 40 hours per week, I’d be paying myself $11.25/hr, taxed way higher than that wage would be taxed if you worked for a company. This doesn’t even account for paying a tech editor to edit the pattern, compensation for test knitters, hiring a photographer, hiring a model, etc. In most all geographic areas in the United States, this is simply not enough income to pay living expenses in a single income, single person household.